《꽃 Flowers》

김민희, 김수연, 안상훈, 이호인, 이혜인, 임노식

2021.5.6.-2021.6.26.

기획 : 권혁규

진행: 허호정

그래픽 디자인: 윤현학

설치: 정진욱

《Flowers》

Minhee Kim, Suyeon Kim, Sanghoon Ahn, Hoin Lee, Hyein Lee, Nosik Lim

06.MAY.-26.JUN.2021.

Curating : Hyukgue Kwon

Curatorial Assistance : Hojeong Hur

Graphic Design : Ted Hyunhak Yoon

Artwork Installation : Jinwook Jung

어김없이 꽃은 핀다. 앞서고 뒤처지는 개화 시기가 어떤 시간을 소란스레 안내하는 까닭은 그럼에도 불구하고 꽃이 핀다는 사실 탓이다. 마스크를 쓰는 틈에도, 고함과 체념, 실소의 나날에도 꽃은 어느새 펴 있다. 그리고 꽃은 진다. 그것은 가장 극적이고 아름다운 방식으로 생의 유한함을 보여준다. 절정은 곧 시들 것을 예견케 하고, 그 찰나는 이중의 시간을 겹쳐 놓는다. ‘어김없이’ 피고 지는 꽃은 회귀와 숙명의 논리 안에서 부활하는 생을, 돌아올 미래를 약속한다. 그래서 꽃을 건네고 받는 일 그리고 보는 일에는 강력한 의미와 상징이 동반된다. 사랑, 축하, 추모 등 피고 지는 여정 사이에서 유한함과 약속을 가시화하는 ‘꽃’은 거의 모든 삶의 의례와 함께 한다.

꽃이 등장하는 그림들이 있다. 전체 미술사를 꽃그림만으로 기술할 수 있을 정도로 미술은 피고 지는 불가항력적 힘을 커다랗게 은유해왔다. 우리는 비너스가 탄생하는 순간 바람과 함께 흩날리는 꽃을 발견하고, 마리아에게 ‘나를 만지지 말라’고 말하는 예수의 발끝에서 빨갛고 하얀 꽃무리를 본다. 밖에 나가 그림을 그리는 일이 관례가 되던 시기에 화가들은 길과 정원에 나서서 맨눈으로 꽃을 그렸다. 회오리치는 마음과 감정을 담았고, 본질적인 것, 가장 근원적인 것을 찾아내리라는 의지로 꽃을 그렸다. 꽃은 아름다움과 생명의 실존으로, 저항과 균열의 상징으로 미술의 역사에 나타났다.

동시에 언젠가 저무는 숙명은 외면 받는 이유가 되기도 했다. 찰나에 쏟는 마음은 세속적 취미나 취향으로 치부되고, 그 정성은 하찮은 기교나 기술로 오해받았다. 18세기 이후 서양미술은 꽃을 장식적인 미술로 간주하기도, 동양의 문인화 전통은 수많은 꽃들, 일례로 탐스러운 모란을 세속적이라며 경시하기도 했다. 동서를 막론하고 많은 꽃그림은 나약하고 속된 것으로 여겨졌다. 그렇게 꽃그림은 낡은 화랑 한 모퉁이를 차지하고, 동네 식당과 미용실 벽을 채운 형형색색의 벽지와 같은 대접을 받았다.

다시 꽃은 폈고 미술은 여전히 꽃을 담아낸다. 거짓 없는 생명으로 피어난 한 송이 꽃을 의미 없다 할 수 있을까. 《꽃 Flowers》은 ‘꽃’과 그 바깥의 윤곽을 사유하는 시도들과 함께 오늘 회화의 면면을 살펴본다. 참여 작가들은 이름과 모양, 종이 다른 꽃들을 저마다의 은유와 방법, 감각으로 추동한다. 전시에서 꽃은 심리적이며 물리적인 한편 사회적인 발화로서 개화한다. 그것들은 흐드러지게 피고 지거나, 발갛게 솟아오르거나, 하얗게 색이 바래있다. 또 밤 불빛 사이로 움츠리고 꿈틀대거나, 가지런히 꽃꽂이 되어 있다. 그렇게 죽은 줄 알았던 욕망을 일깨우고, 개인과 공동체의 숨겨진 사연을 서사화하며 잊혀가는 기억을 끄집어낸다. 저물지만 다시 피고 만다는 준비된 선언으로, 꽃은 스스로와 오늘의 회화를 확인시킨다.

김민희는 직접 본 장면과 그것을 촬영한 사진을 자신의 ‘필터’로 확인하고 재구성한다. 작가에게 ‘필터링’은 이국적인 풍광으로부터 야릇하고 도발적인 판타지를 이끌어낸 <오키나와 판타지>(2018) 연작에서 엿볼 수 있듯 주어진 대상-이미지를 나름의 시선으로 재현, 소유하려는 욕망과 맞닿아 있다. <아젤리아 Azalea>(2021)는 진달래과 중 하나일 것으로 추정될 뿐 그 이름을 정확하게 알 수 없는, 타국에서 본 꽃을 자신만의 필터로 그려낸 것이다. 마치 애니메이션 삽화 같은 작업의 색채와 구성 한편에는 유화 물감의 뚜렷한 질감이 드러난다. 가까이 갈수록 분명해지는 이미지의 질료와 두께는 흐드러진 진달래밭에서 피고 진 꽃송이들의 넘실거리는 생명력을, 알 수 없는 서사와 노스탤지어를 마주하게 한다.

김수연은 불분명한 무언가를 상상적으로 구성하고 현전케 하는 시도로서 회화에 동조한다. 망상과 상상을 물질화하는 과정에서 작가는 주변에서 수많은 이미지를 모으고 조합해 가상의 대상을 만들고, 이를 캔버스에 고스란히 옮겨 놓는다. <꽃, 두 천사>(2017)는 수십 장의 프린트 된 종이를 오리고 붙여서 만들어진 입체 꽃을 회화로 재현하고, <사뿐>(2017)은 ‘춘화’에서 힌트를 얻어, 슬쩍 들린 꽃무늬 치마 깃과 매끈한 신체를 조합해 극화된 장면을 연출한다. 이때의 꽃들은 숨겨진 사랑을, 가 닿을 수 없는 마음을 전하는 꽃말이 되기도 하고, 무언가에 의탁하지 않고 다만 시각적으로 만지고 욕망하는 상태를 암시하기도 한다. 이들은 모두 <홀드미>(2021)에서 영문 알파벳의 수어로 구성된 여섯 글자 “hold me”가 지시하는 바와 같이, 미지의 가상성을 경유해 분명한 현재의 시간과 상념을 붙들고자 한다.

안상훈은 의미와 형상의 어긋남을 좇는 그리기와 이미지에 집중한다. 작가는 본격적인 그리기에 앞서 구글링으로 작업의 명제를 설정하거나 이전 작업의 제목을 가져와 임시적 기호를 마련한다. 낯익은 명제/기호는 이미지의 출발점으로, 해석의 근거로 기능하지만, 더할 나위 없이 추상적이다. 안상훈의 회화는 결국 우연과 필연, 자극과 수용 사이를 오가며 결코 익숙하지도 낯설지도 않은 이미지의 그물망을 형성한다. ‘꽃’의 찰나성은 이러한 작업의 과정에 가닿고 <다시 미소 짓고 싶어>(2021)에서‘장미’, ‘백합’ 등의 기표는 다시 거부되어야 할 임의적 세계에서 피어난다. 이전의 분명함을 덮고 전복하는 색의 운동과 흔적은 추상회화에서 특정 의미와 정서가 어떻게 발현되는지, 순수하게 시각적이고자 하는 열망은 결국 잔여의 지평에서 확인되는 것인지 질문한다.

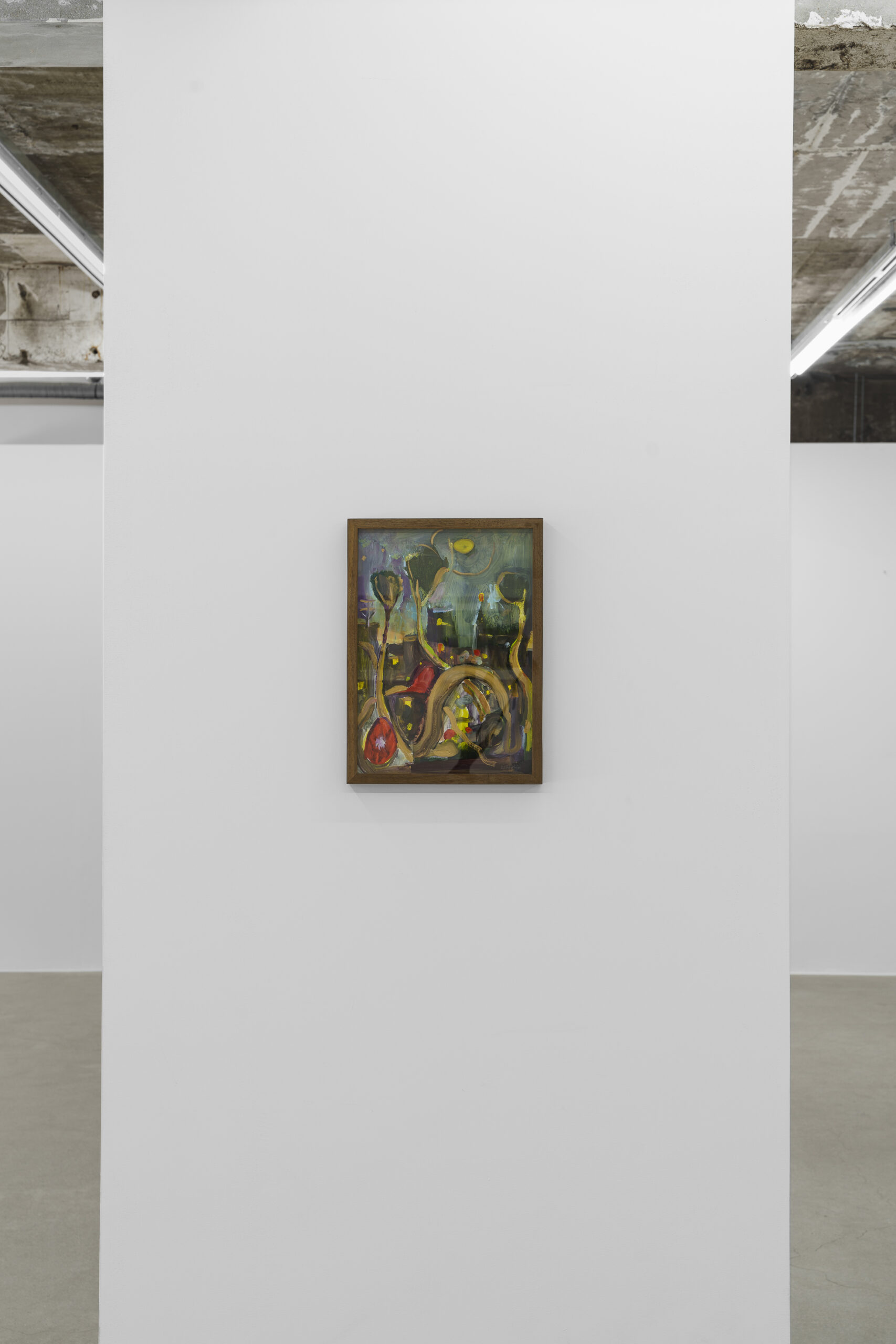

이호인은 특정 상태나 형상이 가시화되는 조건에 역설적으로 응답하는 그림을 그린다. 이를테면, 주로 빛으로 드러나던 풍경을 어둠 속 (불)빛과 색채로 나타내는가 하면, 앞과 뒤, 중심과 주변, 위아래 등의 익숙한 질서가 묘하게 뒤틀린 장면을 연출하며 특유의 생경함과 멜랑콜리를 전달한다. 여기서 꽃과 나무, 식물의 넝쿨은 뒤바뀜과 교차를 예사롭지 않게 지시하며 저 멀리 희미하게 보이는 도시/풍경의 무언가를 회고하고 상상하게 한다. 이번에 선보이는 <옥상 달빛>(2021)은 대낮의 자연이 아닌 달빛이 스미는 옥상에서, 피는지 지는지 알 수 없는 꽃의 움직임을 본격화된 붓질의 흔적으로 가시화한다. 이는 어두운 실루엣과 역광으로 모습을 드러낸 <검은 꽃>(2017)과는 또 다른 방식으로 형상의 존재와 그것의 이중성을 전면화한다.

이혜인은 다양한 장소와 사람, 삶의 맥락이 얽혀 있는 현재로서 자신의 회화를 구체화한다. 여기서 그림 그리기는 주변 인물과 자연 생태부터 저 먼 곳의 타인과 환경까지, 자신의 바깥 세계를 구성하는 대부분의 사건에 관여한다. 전시에서 작가는 외부/타인과의 동화, 혹은 매개의 시도 한가운데에서 꽃을 발견한다. <꽃 구름>(2021)에서 분할된 화면은 작가와 타인이 꽃을 이유로 줌에 접속해 만나는 장면을 보여준다. 스크린 속 꽃은 그것이 놓인 고유한 일상과 공간을, 또 이를 실시간으로 그리고 있는 작가의 시간을 동시에 점유한다. <자연인의 집>(2020)에서도 꽃은 작가가 경험한 자연의 흔적이자, 기억과 감정의 표현물로 등장한다. 야외에서 대상을 직접 담아내는 일종의 사생부터 온라인 영상 통화까지 다양한 방법으로 외부 시공을 연결해 온 작가는 세계 내 존재의 경험으로 회화를 발생시킨다.

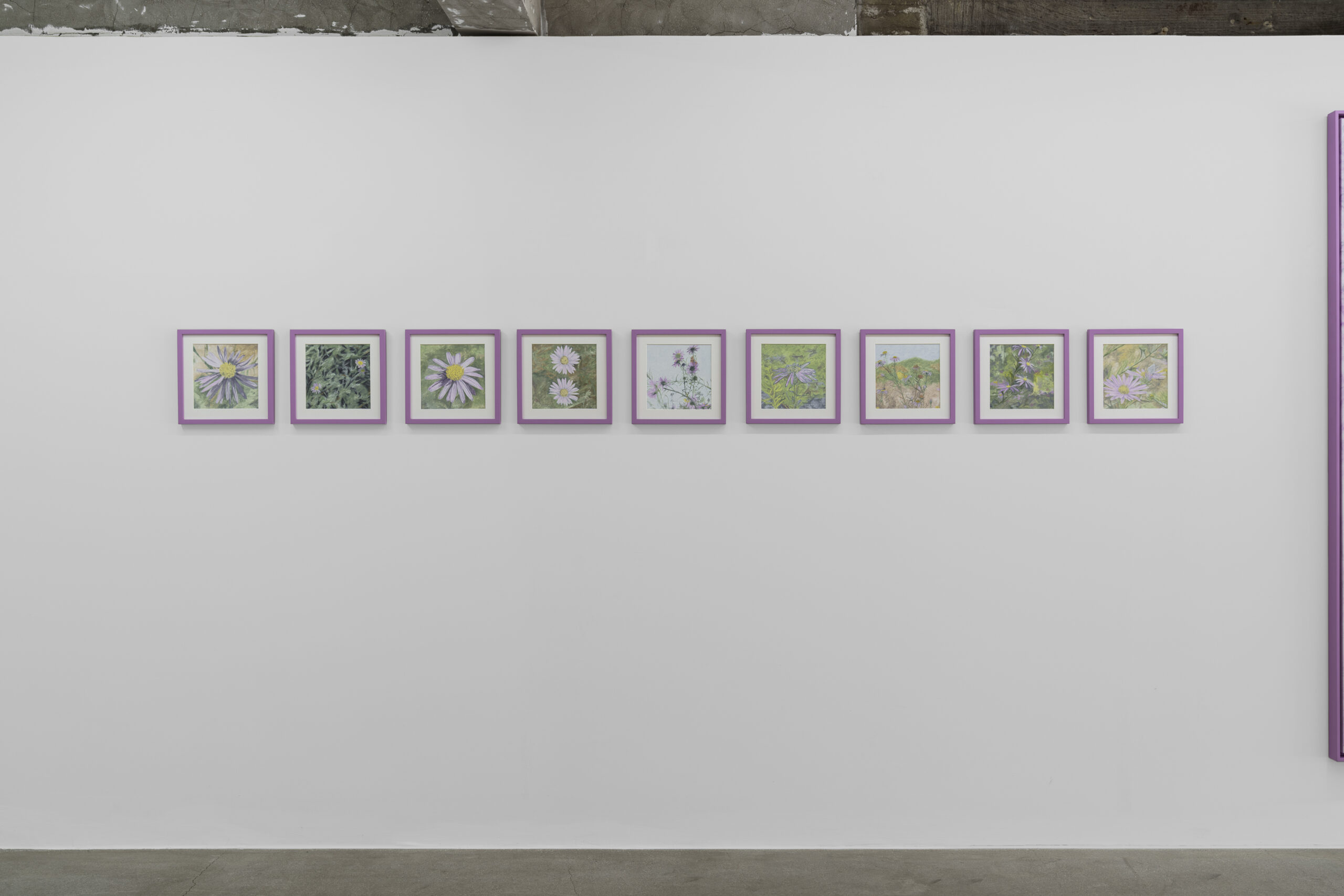

임노식의 그리기는 자신의 삶을 구성해 온 사람과 장소를 거짓이나 과장 없이 대면해 보길 시도한다. 기억과 상상, 재현과 위장을 오가는 이 그리기는 실제와 만나고 다시 어긋나는 이미지의 숙명을 받아들이며 ‘거기 있었던 무엇’과 멀어지고 가까워지기를 반복, 실험한다. <들꽃>(2021)은 작가가 자신의 고향에 위치한 모래산을 직접 찾아 그린 그림이다. 4대강 사업을 진행할 당시 퍼낸 준설토를 쌓아 두며 생겨난 모래산에는 언제부턴가 나무와 풀이 자라는 등 이질적이고 정체가 모호한 사회이자 생태가 만들어지기 시작했다. 작가는 현장을 찾아 어딘지 색이 바랜, 쉬이 이름을 떠올릴 수 없는 들꽃을 마주한다. 어떤 기억과 이야기, 감정은 생의 아이러니를 창백하게 드러내는 꽃에 투사되고, 화면 안에서 꽃은 그에 맞는 색깔과 채도, 프레임과 거리를 갖는 이미지로서 그 나름대로 삶의 궤를 이어간다.

전시는 꽃그림으로 가득하다. 봄날의 꽃 전시는 한철 나들이에 불과한가. 진짜 꽃이 만발하는 계절에, 다만 ‘그려진’ 꽃을 보자고 하면 무모하고 무효한 제안일까. 암술과 수술을 함께 갖춘 자웅동체이자 양성의 꽃은 줄곧 양면적이고 모순적인 의미를 운반했다. 인간의 거의 모든 삶의 여정에 관여하지만 늘 제한된 시간에만 존재했고, 미술의 가장 익숙한 소재임과 동시에 경시의 대상이었다. 하지만 분명한 건 이러한 꽃의 양면성이 지난한 통속성을 뚫고 늘 새로운 삶의 모습으로 등장했다는 점이다. 꽃은 폈고, 그럼에도 불구하고 그려졌다. 꽃이 꽃으로 또 다른 모순을 돌파하려면 단순한 구경 이상의 바라봄이 필요하지 않을까. 꽃의 개화는, 그려짐은 그 바라봄을 온몸으로 요청하는 몸짓이 아닌가. 어슴푸레한 상상의 세계부터 현기증 나는 현실까지 다양한 내용과 형식의 꽃그림은 각 개인과 회화 매체가 스스로를 사고하는 존재론적 탐구의 소산이라 할 수 있다. 이제 꽃을 본다. 다양한 현재의 모습을 발견하고, 이를 동시대 회화의 진행 속에서 확인해 본다. 꽃이 피었다는 사실은 꽤 의미심장하다.

Flowers

The flower blooms—without fail. The “time of blooming flowers” (as the first days of spring are called in Korea), no matter how early or late it may be or however chaotic the subsequent weeks, is an age-old marker of time for that very simple reason: flowers always bloom. They bloom amid our inability to stop wearing masks and days of screaming matches, resignation, and hollow laughter. Then, as surely as they bloom, they fade—the most dramatic and beautiful way of showing the finite nature of a living thing’s existence. Full bloom is a harbinger of fading: therefore, this transient moment is a moment of duality. The flower, with its inevitable cycles of blooming and fading, promises a resurrected life and an ever-returning future from within the logic of returning (as a salmon returns to its birthplace) and destiny. This is why the act of exchanging or viewing a flower is accompanied by powerful meaning and symbolism. The flower, a visualization of finiteness and promise that is represented by cycles of blooming and fading (love, congratulation, commemoration, etc.), can be found in almost all life-stage rituals.

The flower is a prolific motif. It has been used throughout history as a metaphor for irresistible power to the point that books on art history can be written entirely on flower paintings. We see flower petals floating in the breeze at the moment of Venus’ birth and red and white flowers at Jesus’ feet when he tells Mary Magdalene not to touch him. In an age in which it was customary to paint outside, many artists painted the flowers planted along roads and in gardens as they saw them. Their depictions of flowers embody a whirlwind of emotions and a commitment to finding that which is fundamental. Flowers have, throughout the history of art, served as a visualization of beauty and life as well as a symbol of resistance and fissure.

The flower, at the same time, was cast aside for its limited lifespan. A painstaking rendition of a flower was denigrated as a “worldly” pastime, with the dedication invested in creating them misunderstood as an amateurish concern. Post-18th century Western art regarded the flower as merely decorative art, while the literary paintings tradition of East Asia belittled countless flowers (for example, the lush peony) as “worldly.” As such, the flower painting tradition of both the East and West has a long history of being regarded as weak and vulgar. It is in this way that flower paintings began occupying the most remote corners of aging art galleries and became equated with the gaudy, flower-decorated wallpaper found at neighborhood restaurants and beauty parlors.

Today, the flower is again in full bloom in multiple genres. Can we dismiss a single flower, which has come out of the ground with an unstoppable, unaffected energy, as worthless? Flowers explores the state of contemporary painting along with attempts to consider the flower and what lies beyond its conceptual boundaries. Six artists bring to life flowers of different names, shapes and species through their unique metaphors, techniques, and sensibilities. In this exhibition, the flower blooms psychologically, physically, and, at times, socially. They are in full bloom, fading, healthy and red, or wilted and dry. At other times, they are huddled between the city’s nighttime lights, trying to squirm free, or stock-still in a bouquet. It is in such ways that the flowers awaken desires that we thought were dead and bring forth long-forgotten memories by creating discourses out of the hidden stories of individuals and communities. Through their declaration, which was prepared long before, that they may fade but will definitely bloom again, and the flower reawakens us to its existence as well as to the possibility of 21st century painting.

Minhee Kim reconfigures things she has seen “in reality” and photographs of such things through a very personal filter. For the artist, filtering, as can be seen in the OKINAWA FANTASY (2018) series (which draws out erotic, suggestive fantasies from exotic landscapes), is closely linked to the desire to reenact subject matter in her own possessive way. Azalea (2021) depicts a flower that the viewer assumes is from the family Ericaceae but that we, in fact, cannot know because it is a flower that the artist saw overseas that has been “filtered.” The animated film illustration-like color palette and composition of Kim’s artworks also have an oil paint-like materiality. The texture and dimensionality of the figures in her works, which come into sharper focus the closer you get to the artwork, bring us face-to-face with the vitality of a field covered in fully-bloomed azaleas, the narrative that they embody is something that we cannot know the details of, and evokes an equally unfamiliar nostalgia.

Suyeon Kim’s paintings are attempts to translate into real-world language her imaginings of vague concepts. In the process of materializing such delusions and imagination, Suyeon Kim collects countless images from her surroundings, with which she creates virtual beings and brings them to life on the canvas. Blossom, Two White Angels (2017) is a painting of flowers that appear three-dimensional because they were made by cutting and pasting pieces of printing paper. The Soft Step (2017), which is inspired by the traditional genre of erotic painting (chunhwa), creates a dramatic scene by combining the edge of a slightly-lifted flowery skirt with a bare shin. The flowers are both a symbol of unrequited love and a state of visual desire that is not linked to any particular emotion. All of these, similar to what is implied by HOLD ME (2021) in the six letters of the title represented in American Sign Language, strive to hold onto the very concrete concerns of the present through the virtual-ness of the unknown.

Sanghoon Ahn concentrates on images and a mode of illustrating in which shape and meaning never coincide. Before he starts painting, Ahn decides on the title via Google search or borrows the title of a previous artwork as a temporary title. It is in this way that vaguely-familiar titles and symbols become the starting point of an artwork. They offer a few wisps of grounds for interpretation, but cannot change the abstractness of Ahn’s work. Ultimately, Ahn’s paintings are a web of images that are neither familiar nor unfamiliar that vacillate between chance and destiny and stimulation and acceptance—in this way, embodying the transience of the flower. The roses and lilies in Smile Again (2021) bloom, but in an arbitrary world in which they will soon, yet again, be cast aside. The artist asks how movements and traces of color, which overthrow the past’s concreteness, realize certain meanings and sentiments in the genre of abstract painting. Ahn also asks whether passion that wants to be purely visual can eventually be seen in the realm of the vestige.

Hoin Lee’s paintings respond paradoxically to situations in which a particular state or shape come into clear view. For example, Lee depicts sun-lit scenes with light and colors that are applied as if it is dark. He also conveys a sense of alienness and melancholy through scenes that delicately twist familiar orders (e.g. front and back, center and periphery, top and bottom). Chaotically-jumbled flowers, trees and other plants, through switching and intersection, make us recall and imagine something in the barely-visible hint of a city or landscape far away. Moonlight (2021), as its name suggests, depicts a rooftop drenched in the light of the moon (not the sun), gives life to the movements of flowers that can be blooming or fading through unique brushwork. It brings our attention to the existence of shapes and their duality in a way that is very different from that of Black Flower (2017), in which we can distinguish the outline of the flower because it faces away from us, with the sun shining on its front.

Hyein Lee grounds and contextualizes her paintings in the present, which is a context-free jumble of locations, people, and lives. For Lee, the act of painting is way to intervene with her acquaintances and immediate environment, and people and environments that are faraway, and most of the events that comprise the world outside her environs. For this exhibition, Lee discovers flowers in the points at which we are assimilated with the outside world/others and experimental endeavors on painting. The partitioned backdrop in Flowers and Clouds (2021) is of a Zoom meeting between Lee and several acquaintances that was called to discuss their flowers. The online sharing of flowers and their real-time environments is juxtaposed with the temporal world in which Lee is creating this painting. The same is true of the flower in The Countryman’s House (2020), where it is both a remnant of nature as it was experienced by Lee and a visualization of memory and emotion. Lee, who has spent much of her career linking disparate spatio-temporal realms through everything from “sketches” in the traditional sense (drawing the subject while outdoors) to online video conferences, produces paintings through experiences that are concrete in the world they are from.

Nosik Lim’s paintings invite us to come face-to-face with the people or places, without fabrication or exaggeration, that make up or have shaped our lives. Lim’s style of painting—which vacillates between memory and imagination, reenactment and camouflage—accepts the destiny of the image to constantly meet and then fail to coincide exactly with the real, repetitively experimenting with the act of being close to and far apart from a “certain something that used to be there.” Wildflowers, Held Their Breath (2021) was painted by Lim at a sandy hill near his hometown. The hill, which is made up of layers of dredged soil that were brought there during the Korean government’s Four Rivers project, began, from a certain point, to be a society and ecosystem with a value, conflicting identity (as can be seen from the trees and grass that grow from it today). At the sandy hill, Lim came face-to-face with a nameless, faded wildflower. Some memories, stories, and emotions have been projected onto the flower, which visually embodies the irony of life. The flowers in Lee’s painting live out their lives, albeit unconventionally, as images that are far from the colors and dimensions of their real-life counterparts.

The exhibition is full of flower paintings. Is this therefore an art exhibition about flowers (on a spring day) nothing more than that—a fun, one-time event? Is the viewing of painted flowers in a season in which real flowers bloom a meaningless activity? The bisexual flower, which has both pistil and stamen, has always implied self-contradiction and duality. It only existed for a very short window of time, despite its presence in almost all areas of human life, and was simultaneously one of the most familiar of motifs and the subject of disdain. What is clear is that the duality of such flowers always managed to pierce convention and reemerge in our lives in new ways. For this exhibition, flowers were depicted mostly in bloomed state. Is there not a need, for the flower to transcend its inherent inconsistencies, for us to view flowers as something more than a springtime amusement? Are not the flower’s blooming and artistic visualization both acts that ask us, fervently, to view them in a way that is not as springtime amusement? The flower paintings, each characterized by a different format and content—from the dim world of the imagination to our current, vertigo-inducing reality—are each the outcome of their own existential ponderings. We see a world of flowers. We see diverse aspects of the here-and-now as they exist in the world of contemporary painting. It is why when we say: “the flowers have bloomed,” we are making a statement that is loaded with meaning.

Kwon Hyukgue, Hur Hojeong