《인공 눈물》

2024.02.15.-04.13.

김문기 박세진 양지훈 윤희주 이목하 최윤희 추수 허수연

기획ㅣ허호정

진행ㅣ도혜민

그래픽 디자인ㅣ프론트도어

설치ㅣ조재홍, 염철호

기술지원ㅣ김규년(뉴뉴미디어)

주최/주관ㅣ뮤지엄헤드

후원ㅣ한국문화예술위원회, 2024 시각예술창작산실

에필로그ㅣ김유림

𝑨𝒓𝒕𝒊𝒇𝒊𝒄𝒊𝒂𝒍 𝑻𝒆𝒂𝒓𝒔

Feb.15.-April.13.2024.

Moongi Gim, Sejin Park, Jihoon Yang, Hiju Yoon, Moka Lee, Yoon hee Choi, TZUSOO, Suyon Huh

Curated by Hojeong Hur

Curatorial AssistantㅣHyemin Do

Graphic DesignㅣStudio front-door

Artwork InstallationㅣJaehong Jo, Chulho Yeom

Technical SupportㅣKyunyun Kim(Knew New Media)

Hosted and Organized by Museumhead

Supported by Arts Council Korea, 2024 ARKO Selection Visual Art

《인공 눈물》은 ‘우는 얼굴’과 ‘눈물’의 옛 도상들을 떠올리며, 상실과 슬픔을 매개하는 오늘의 이미지를 성찰한다.

저기, 오래된 눈물의 이미지들이 있다. 눈물 짓는 성녀, 울부짖고 일그러진 다면체 얼굴, 유리 눈물이 맺힌 커다란 눈망울, 젖은 눈가를 손으로 훔치는 금발의 여인, 화장이 번진 얼굴로 눈물 흘리는 팝스타….[i] 대개 여인의 모습으로 드러난, 옛 그림의 우는 얼굴을 마주할 때, 사람들은 그 눈물의 의미를 읽어낼 수 있었다. 예수의 죽음, 지난 시대(/예술)의 종말, 떠나간 연인, 배신과 조롱의 로맨스 드라마…. 우는 얼굴 앞에서 사람들은 잃어버린 무엇을 함께 떠올렸고, 그렇게 상실을 분유하는 공동체를 떠올릴 수 있었다.

여전히 많은 눈물의 이미지가 있다. 사람들은 카메라 앞에서 울음을 터트리고, 죽은 이의 이름을 부르거나 불안을 호소하며 눈물을 라이브로 송출하고, 동조를 표하기 위해 우는 표정(😢😭)을 눌러 전송한다…. 하지만 지금 화면을 채우고 있는 이 우는 얼굴들은 저 ‘우는 얼굴’의 역사적 계보를 따르지 않는다. 오늘날 눈물의 이미지는 상실을 상기시키지 못하고 타자를 불러 세우지 않는다. 물론, 그것을 해석할 공통의 방식도 더는 없어 보인다.

한편에선 매일같이 타자의 죽음이 전시된다. 온갖 잣대로 지탄받고 떠난 연예인, 도시의 되풀이되는 참사, 폭력의 피해, 가깝거나 먼 나라의 전쟁, 자연재해…. 그 반대편에서, 살아남은 자들의 이미지가 눈물 짓는다. 이제 눈물의 이미지는 무엇을 보여주는가? 이미 카메라를 향하고 있는, 스스로를 향해 눈물 짓는 이미지는 자기-중심적인 감정을 격발하고 곧 휘발된다. 그러는 동안, 상실을 둘러싼(혹은 상실의 의미를 둘러싼) 여타의 감정과 사유가 엉켜들 계기는 마련되지 않는다. 잃어버린 자를 향한 분노(‘날 두고 떠나다니!’), 상실의 이유를 따지는 차가운 판단(‘무엇이 그를 데려갔을까?’), 뒤늦은 후회와 의심과 부정(‘그는(나는) 내게(그에게) 무엇이었을까?’)이 한 가지로 수렴한다. 이때, 상실은 그것의 주인인 타자를 잃는다.

어쩌면 오늘날, 상실은 부정되고 있는지도 모른다. 끊김 없는 접속의 시대에(누가 온오프라인의 완벽한 단절을 말할 수 있는가?) 생과 사의 단절은 모호해지고, 돌이킬 수 없는 최종성은 상상되지 않는다. 죽은 이의 소멸하지 않은 SNS 계정이 댓글로 갱신되고,[ii] AI로 되살린 죽은 자의 표정과 목소리가 지난한 애도 과정을 순식간의 충격으로 대체한다.[iii] 잃어버린 타자 대신 결여된 자아가, 최종성을 잊은 되살아남이 오늘의 이미지를 채울 때 애도는 서둘러 봉합되거나, 나중을 기약한다.

다시, 저 우는 얼굴의 역사적 도상을 떠올려 보자. 거기 강조된 것은 단절이었다. 눈물의 이미지는 말없는 저쪽의 영원한 닫힘을 확인시켰고, ‘남아있는’ 이쪽이 떠난 자가 ‘남긴 것’을 매개로 —비로소 그를 통해서만— 새로워짐을 상기시켰다. 완전한 이별이라는 사실: “네가 더는 보지 못하는 것들을 그들은 본다. 네가 더는 듣지 못하는 것들을 그들은 듣는다. […] 단순한 것들의 기쁨이 네 슬픈 기억의 빛을 받고 그들 앞에 나타난다. 너는 이 검지만 강렬한 빛이고, 너의 밤으로부터 그들이 더는 보지 못했던 낮을 새롭게 비춘다”[iv]….

돌이킬 수 없는 이별과 지나간 시간의 무게를 어떻게 다시 짊어져야 할까? 이미지 앞에 속도를 줄이고 멈춰 서서, 과거의 두께, 타자들의 크기, 유한자(the finite)로서 우리의 본질적인 취약성(vulnerability)을 사유할 수 있을까? 전시 《인공 눈물》은 이미지들에 둘러싸인 동시대가 상실을 다루고 애도를 지속하는 방법을 망각한 것은 아닌지 질문한다. 그리고 달아나는 이미지와 붙잡는 이미지, 소멸할 수 없는 존재와 영영 돌아오지 않는 존재, 늘 접속 중인 상태와 그것을 끊어내는 상태, 무한한 현재와 지나간 시간 사이의 긴장을 목도하려 한다.

무엇보다도 《인공 눈물》은 미술의 역사로부터 시간을 남기는 습관, 타자의 흔적을 간직하는 전통, 그리고 오래된 것에서 도래할 무엇을 예비하는 태도를 되새긴다. 전시는 여덟 명의 작가가 각자의 상실과 과거를 다루는 방식을 관찰한다. 그럼으로써, 돌이킬 수 없는 이별을 확인하고, 살아남음의 오늘을 타자에 비추며, 슬픔의 사태가 동질화되는 것을 거부하는 이미지를 지금 이곳에 재생할 수 있을지 묻는다.

추수는 2022년작 〈나는 이곳을 졸업하는 것이 부끄럽다〉를 다시 제작해 선보인다. 이는 작가가 독일의 슈트트가르트에서 수학하던 당시, 유럽연합(EU) 외 국가의 출신 학생들에게 차별적으로 등록금을 인상하는 학교 정책에 반발하며 내세운 일종의 성명이자 졸업 작품이다. 이미지의 중심에는 눈물을 뿜어내는 인물이 있다. 과장된 눈물의 주인공은 작가의 분신인 ‘에이미’로, 추수는 AI 데이터 생성의 자율성 내지 창발성을 인정하며 가상 공간의 인플루언서로 활동하는 에이미를 반(半)-주체로 인정한다. 말하자면, 이쪽 세계에 추수가 있고 저쪽 세계에는 에이미가 있는 것이다. 추수와 에이미가 이원적으로 그러나 동시에 작동할 때, 저쪽 세계를 경유해 이쪽 세계에 개입하려는 작가의 시도는 최종성을 상실한 시대의 증상을 운반하는 것 같다. 이때, 현실 쪽으로 방향을 돌려 개입을 시도하는 아바타는 스스로의 과잉된 가상을 결국 현실로 만들게 될까? ‘눈물이 홍수를 이룬다’는 말처럼, 이미지 속의 물줄기는 이윽고 공간의 수조를 채운다.

양지훈은 현실과 가상 또는 실제와 환영이 맺는 관계가 맞이한 (어쩌면 아주 오래된) 역전을 동시대의 풍경에서 발견한다. 작가가 〈테이큰〉(2023)에 삽입한 문장, “사진을 위해 산불이 있다”는 이를 단적으로 시사한다. 당해연도 촬영된 ‘산불 사진’에 한해 시상하는 ‘산불방지 캠페인’이나, 붕괴와 폭발이 만드는 “결정적 순간”처럼, 일어나지 말았어야 할 일을 동력 삼아 그것의 되풀이를 담보하는 이미지가 창궐한다. 양지훈은 이미지가 참상을 재현하는 것이 아닌, 이미 그것이 참상을 견인하고 있는 현상을 지적한다. 또, 현실과 상(像)이 착종된 오늘, 비극 역시 한 가지 풍경(단일 현실의 일반 이미지)으로 소비됨을 확인한다. 나아가 그는 〈dox〉(2023) 연작에서 현실 또는 진실과 무관해지는 이미지의 틀을 가지고 논다. 영상이 무한히 업데이트되는 SNS의 한 창구에는, 출력된 화면의 비율이 교묘하게 조정된 채 콘텐츠가 잘리고 복제된 것을 쉽게 찾아볼 수 있다. 이때 ‘화면비’ 조정은 원본 영상을 그대로 옮길 시 생기는 저작권 등의 문제를 피하기 위해, 복사본을 원본과 다르게 인식되도록 하는 일종의 트릭이다. 심지어 프레임의 각도를 비튼 경우, 여백에 해당하는 검정 레터박스가 ‘박스’형이 아니라 삼각형이 되는 지경에 이른다. 비대하게 모양도 달라진 레터박스는 그 자신의 몸집을 전시한다.

윤희주는, 화면 속 세계를 현실과 길항의 관계에서 이해하는 양지훈과 달리, 둘을 연장 또는 갱신의 관계로 접근한다. 작년 개인전을 통해 처음 선보였던 〈실리 힐리 밀키 쇼〉(2023)는, 현실에서 삶의 의미를 잃어버린 화자가 가상 세계로 넘어와 두 번째 삶을 구축하는 이야기다. 현실에서 잃어버린 삶이란, 추종하던 밴드의 해체일수도, 업무과중(“과로사”), “자살 당하[기]”, 22년 11월 5일[v]이라는 데드라인일수도 있다. 어떻든 각자의 이유로 이곳으로 넘어온 이들은 서버에서 제공하는 아바타 중 하나에 아이디를 입력하고 입장해, 제안된 가치들에 복무를 시작한다. 새로운 아이덴티티, ‘지지zizi’는 텅 빈 세계, 생기도 반응도 없어 보이는 그곳을 달린다. 그런 한편, 현실의 무너짐에 값하는 비용으로 이곳이 세워진다는 점을 감지한다: “연대를 알고리즘으로 착취해 막대한 서버 비용으로부터 도망치는 건 아닌가요?”, “공유는 그 자체로 개체가 이용하는 화폐가 된다.” […] “혹시 공유가 인간성을 의미하나요?”. 하지만 잃어버리는 일의 비용 치르기를 의심하면서도 그는, 여기서 회생하는 (현실에서 상실된) 자를 향해 환호를 멈추지 못한다.

이목하의 〈눈물의 표면장력〉 시리즈는 다소 부자연스러운 미소 뒤에 팽팽한 긴장의 파토스를 머금은 인물을 보여준다. 작가는 왈칵 쏟아질 듯한 눈물을 안으로 삼키던 어린 시절을 회상하며 인물의 표정을 그렸다고 했다. 작가 자신의 얼굴과 닮게도 보이는 그림 속 얼굴들은 대개 SNS를 통해 발견된 것이다. 이목하는 네트워크 속 익명의 인물에게서 초상권 이미지를 구입해 이를 그림의 모티프로 삼는다. 초상의 모델이 작가 자신과 일상적 관계를 맺고 있는 이가 아니라는 점, 그리기의 과정 중에 실제로 그와 만날 일이 없다는 점 등은 대상을 핍진하게 그려내야 한다는 초상 전통의 오랜 압박을 덜어주는 듯도 보인다. 아니, 애초에 그러한 목표가 결여된 채로 진행되는 작업 과정에서 작가는 작금의 관계 맺기가 가지고 있는 자기투사의 일방향성을 확인하기도 한다. 말하자면, 이목하의 인물화는 한 개 자아가 투영된 동일한 이미지들에 다름 아닌 것이다. 작가는 타자를 타자로 수용하기가 원천 차단되는 환경을 염두에 두고, 또 그러한 조건 위에 만들어지는 얼굴의 이미지를 관찰하고 있다. 한편, ‘동시대 초상’으로서 이목하의 그림은 회화적 깊이를 탐구한다. 아주 엷게 유채를 여러 층으로 겹쳐 그린 그림은, 매끈한 표면 대신 안쪽으로 물기를 머금고 들어간 침투의 방향을 제시한다. 어쩌면 눈물은 자기투사의 “표면장력”을 이겨내고 이질성의 세계를 허락할지도 모르겠다.

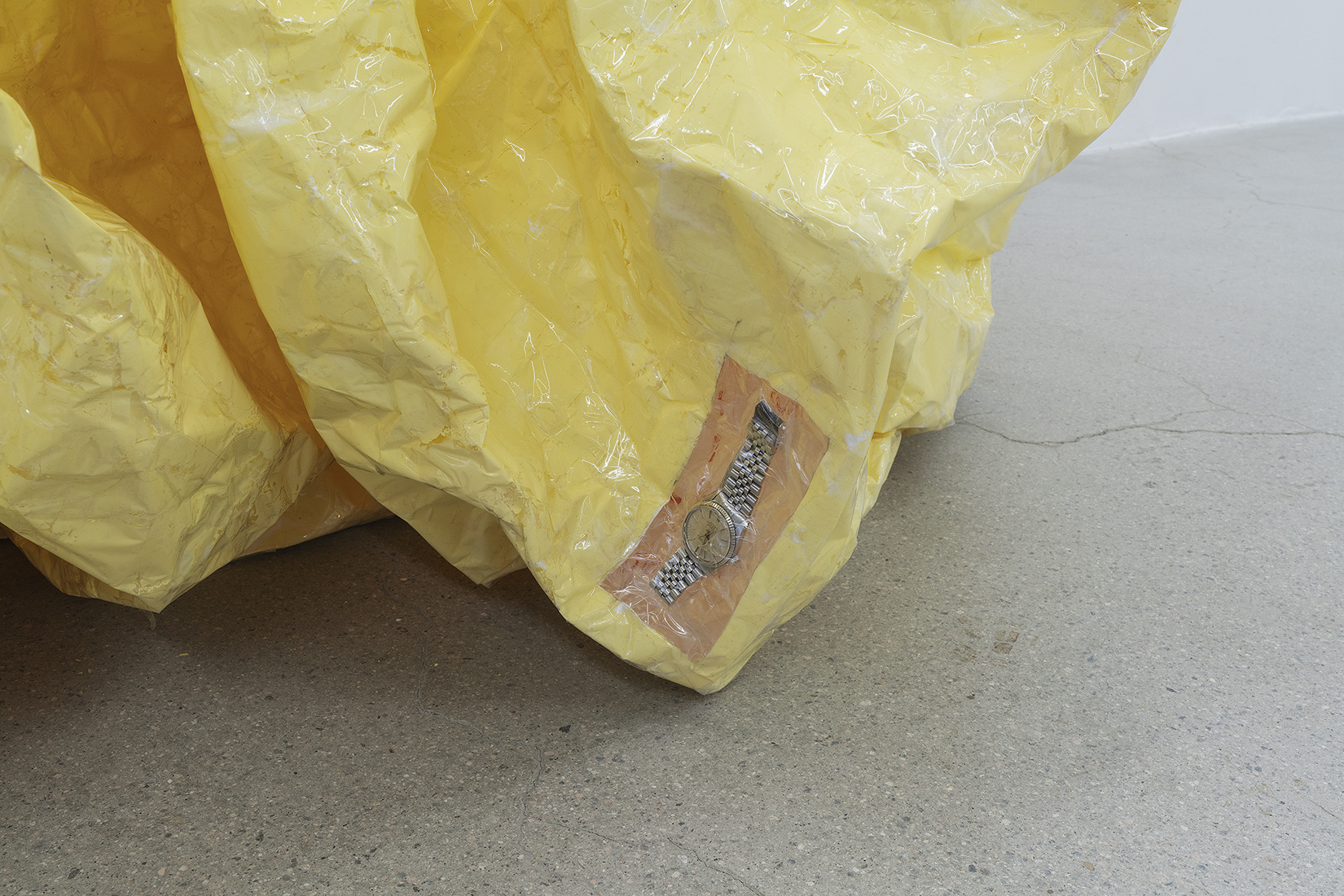

김문기는 전시장의 중앙을 가로막고 선 거대한 조각 〈진리〉(2024)를 선보인다. 조각은 종이의 연약함과 사소함을 드러내며 무게없이 몸집을 키운 채 “총체적 덩어리”로서 미지의 정동을 증폭하고 있다. 방 하나를 가득 채울 면적의 종이를 잇고 스카치테이프로 마감하면서, 작가는 ‘구겨짐’의 임의성과 재생불가한 흔적을 조각적 요소로 포함한다. 〈진리〉는 기존 작업인 〈지혜〉(2022)를 재작업한 것으로, 원 표면을 도료로 커버업하면서 새로 생겨난 크랙은 표층 아래 〈지혜〉의 이미지/말을 간간이 드러낸다. 특징적이게도 이 조각에는 일상에서 수집한 작은 사물(감자칩, 막대사탕, 할아버지 손목시계 등)이 덧붙어 있어, 오래되고 하찮은 사물들에서 “지혜의 암호”[vi]를 찾는 벤야민적 애착을 떠올리게도 한다. 〈타바스코 시리즈〉(2024)는 김문기가 자기 작업을 이르는 말인 “가난한 조각”의 개념적 틀을 유지하고 또 구체화하는 새로운 작업이다. 여기서 작가는 재료의 의미를 보다 강조한다. 가령, 포스트-잇으로 대표되는 접착식 종이는 “붙이면 만큼 이루어진다!”는 제품의 브랜드 표어처럼, 동시대 한국 사회에서 특별한 의미를 갖게 되었다. 그것은 최애의 사진이 걸린 공공장소를 순례하거나, ‘나일 수도 있었던’ 희생을 기리거나 사회의 부조리를 고발하는 데 참여하는 한 방편이 되기도 한다. 작가는 포스트잇을 켜켜이 쌓아 형을 만들고 “찰나를 붙드는” 순간접착제로 고정하며, 가능한 의미들을 단단한 조각으로 변모시킨다.

허수연의 작업에서 물성은 매끈하지 않은 표면과 레디메이드 오브제로 강조되며, 두터운 서정성을 풍긴다. 특유의 표면을 만들기 위해 작가는 종이죽을 만들어 사용한다. 그는 자기 집으로 매달 배달되는 잡지들을 모아두었다가 면면을 직접 손으로 찢고 물에 불렸다. 그리고 물에 흐드러져 죽이 된 것을 평면 지지체나 주워 온 사물 위에 덕지덕지 붙였다. 짓이겨진 종이가 수분을 덜고 안료와 합쳐져 굳어갈 때, 작품 표면에 두드러지는 요철은 ‘표면의 입체성’이라는 역설을 경화된 고체의 ‘치덕치덕한’ 액체성으로 환기한다. 그렇게 물성 자체가 가지고 있는 표현적 효과를 응용하며 작업은 천천히 의미를 발생시키고, 허수연은 고자극 ∙ 고효율의 이미지 수요와 소비지상주의가 인간성을 추월하는 현재를 주시하면서 그와 반대로 작동하는 이미지를 고민한다. 이번 전시에서는 〈설명할 수 없는 좌절에 대해〉(2024), 〈아무것도 모르는 것처럼 또는 의식하지 않는 것처럼〉(2024)을 통해 좀 더 직접적으로 서사의 의지를 드러낸다. 〈아무것도(…)〉(2024)는 한 인물을 등장시키며, 스스로의 비극마저 편집된 프레임 속 대상으로 마주해야 했던 누군가의 현실을 유리상자 안에 극화한다. 〈설명할 수 없는(…)〉(2024)은 언어를 경유하고 또 그것을 웃돌기 마련인 슬픔의 이미지를 뒤집힌 우산으로 형상화한다. 두 작품은 관객으로 하여금 소비재가 된 타인의 죽음과 그러한 죽음을 앞당겨 녹화한 장면을 바라보게 하면서, 제목을 달 수 없는 감정을 좀 더 구체적으로 마주하도록 요청한다.

최윤희의 〈원래의 땅(course 1)〉(2021)은 시간의 풍경을 보여준다. 작가가 연중 365일을 걷는다는 산책길의 담벼락을 그린 그림은, 그러나 특정 공간과 주위 풍광을 (전통적 의미에서) 재현하지 않고 대신 보이지 않는 시간을, 거기 담긴 감각과 기억들을 담는다. 작가가 “새로움보다 일상성에” 더 가치를 둔다고 말한 것도 우연은 아닐 텐데, 〈원래의 땅(course 1)〉(2021)은 반복을 미덕 삼는 일상성의 시간을 흔적으로 남겨 펼쳐 보인다. 흔히들 회화가 시간을 기록하는 매체라고 말할 때, 이는 평평한 지지체 위에 안료를 시간 순으로 쌓아 층을 만든다는 물리적 원리를 지적하는 것이다. 하지만 최윤희의 회화에서 시간을, 시간의 풍경을 말하려면, 표면에 표면을 덧대는 적층의 구조를 떠올려서는 안 된다. 물론 작가는 커다란 캔버스 위에 형상을, 때로는 글과 말을 시시때때로 얹고 그 위를 또 다른 것들로 덮곤 했다. 하지만 이때 그리기는 이미지의 층이 두께를 채 얻기 전에 안쪽으로 파고 들게 하는 일이었다. 그는 천에 물감을 흡수시키고자, 수건이나 큰 붓을 이용하거나 맨손으로 물감을 밀어 넣어 표면을 지나간 무엇이 안쪽으로 가라앉게 만들었다. 화면이 투명해 보이는 것은 이렇듯 안료가 표면에 두께를 더하지 않고 반대로 스며들었기 때문이며, 화면에 뿌연 안개가 드리운 듯 보이는 까닭은 그러한 스며듦이 반복되었기 때문이다. 물리적 실체가 기화한 듯한 이러한 회화적 표현은 지나간 시간을 그림에 붙들어 놓는다. 그리고 표면 아래 침잠된 시간의 무게는 평면을 지탱한다.

박세진은 꾸준히 풍경을 연구해 왔다. 이때, 풍경은 그리기의 과정을 통해서만 모습을 드러내는 “다른 삶”이자 보존된 기억의 형태를 담는 것을 말한다. 달리 말해, 박세진의 풍경화는 구체적인 장소를 지시함에도 불구하고, 그때 그곳이 “그림의 바깥에서[는] 돌이킬 수 없는”, 또한 작가 자신과도 분리할 수 없는 ‘그려진 풍경’임을 확인시킨다. 이번에 선보이는 ⟨반나절⟩(2024)은 2020년부터 진행 중인 〈여름_너〉 연작의 하나로, 〈여름_너〉는 특별한 일은 고사하고 아무런 사건이 일어나지 않았던 어떤 여름 날의 한 장소를 담는다. 다만, 특기할 만한 점은 그날 그곳에 비가 내렸다는 것이다. 작가는 강원도 원주의 가로등도 인적도 드문 레지던시에서 지내며, 밤이면 칠흑 같은 어둠 속에 아무것도 볼 수 없던 창밖 풍경의 변화를 지켜보았다. 어느 날, 찌는 더위 중 비가 갑자기 쏟아지던 날, 박세진은 비가 내려 젖은 길이 희미한 빛을 반사하며 주변 형상을 드러낸 것을 기억한다. 〈여름_너〉는, 누군가 지나가는 모습이 (마침내) 보이던 그 밤, 비가 쏟아지기 직전의 그 저녁, 아스팔트 길을 맨발로 뛰어내려가 보았던 그 낮을 시간의 역순으로 재구성한다. 〈반나절〉은 그중 낮 시간을 그린 작품이며, 연작의 첫 발표 이후(2020년) 한동안 그리기를 중단했던 작가를 복귀시킨 그림이기도 하다. 작가는 “생의 유한함에 여전히 어찌할 바를 모[르던]” 때를 지나, 그리기를 다시 시도하며, 지나간 그때를 품고 현재의 그림에 남은 한 장소와 자신을 이어 나간다.[vii]

기획/글 허호정

[i] 나는 다음과 같은 그림들을 떠올린다. 진위와 정당성의 여부를 떠나 눈물의 강력한 감상을 일으키는, 여자들의 초상: 〈십자가에서 내려지심〉(1435, 로히어르 판 데르 베이던), 〈참회하는 막달라 마리아〉(1550, 티치아노), 〈(유리) 눈물〉(1932, 만 레이), 〈울부짖는 여인〉(1937, 피카소), 〈우는 여인〉(1964, 로이 리히텐슈타인), 〈무제 필름 스틸 #27〉(1979, 신디 셔먼)….

[ii] “‘너랑 못 본지도 오래 됐네. […] 너랑 같이 있었으면 좋겠다! […]’ 이런 말들 속에는 순진한 자기 만족이 얼마나 담겨 있을까? [누군가의] 죽음이라는 최종성을 해맑게 무시해 버리는 ‘귀여운 연기’는 또 얼마나 담겨 있을까? 그 일이 돌이킬 수 없는 일이라는 사실을 받아들이지 않는 태도”, 마리아 투마킨(서제인 옮김), 『고통을 말하지 않는 법』(서울: 을유문화사, 2023), 62.

[iii] “숨진 가족 목소리 되살린다… 아마존 AI ‘음성 복제’ 신기능 논란”(2022년 6월 24일, 『연합뉴스』: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/MYH20220624014100704), “엄마, 보고 싶었어요” 순직 조종사, AI로 부활”(2023년 7월 6일, 한지혜 기자, 『중앙일보』 정치-국방면: https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/25175173), “설특집 VR다큐 ‘너를 만났다4’ … 13살에 떠난 아들 16살로 만난다”(2024년 2월 11일, 진향희 기자, 『매일경제』: https://www.mk.co.kr/news/hot-issues/10940518).

[iv] 에두아르 르베(한국화 옮김), 『자살』(서울: 워크룸 프레스, 2023), 33.

[v] “이태원 참사: 국가 애도 기간 마지막 날도 이어진 추모의 발길”(2022년 11월 5일, 『BBC NEWS 코리아』: https://www.bbc.com/korean/news-63524957).

[vi] 수전 벅 모스(김정아 옮김), 『발터 벤야민과 아케이드 프로젝트』(서울: 문학동네, 2004), 222.

[vii] 따로 인용을 표하지 않은 경우, 서문에서 큰따옴표(“,”) 처리된 문장은 모두 해당 작가의 말에서 왔다.

Artificial Tears

Recollecting the conventional icons of “crying faces” and “tears,” Artificial Tears reflects on the images of today that mediate loss and grief.

There lie crying images of the past. A tearful saint, a distorted polyhedral face howling, large eyes with glassy tears, a blonde woman wiping one’s wet eyes with her hand, a crying pop star with her makeup smudged…[i] When facing crying faces of old paintings, usually presented through a woman’s face, audiences were generally able to read the meaning behind the tears. The death of Christ, the end of an era, a lover who left, romance dramas on betrayal and ridicule, etc… In front of a crying face, people could recall something each had lost, enabling them to think of a community that shares the loss.

There are still numerous images of tears. People burst into tears in front of the camera, calling those who have passed away, pleading anxiety, broadcasting their sorrows live, and viewers transmit crying emojis (😢😭) to pay their sympathies… However, these crying faces occupying the screen do not follow the historical genealogy of “crying faces.” The image of tears today fails to bring up loss or call back others. Naturally, a common method of interpretation no longer seems to exist.

On one hand, the deaths of others are on display every day. A celebrity gone, condemned by various standards of the public, recurring disasters within cities, damages from violence, war in countries both near and afar… On the other hand, images of those who have survived are filled with tears. Now, what do these images show? Already facing the camera, the image cries towards itself, bursting out self-centered emotions, and soon volatilizes. Meanwhile, there is no opportunity for other emotions and thoughts to intertwine regarding loss (or the meaning of loss). Anger towards those who are gone (“How can you leave me alone!”), cold assessments on the reasons behind such loss (“What took you away?”), belated regrets, doubts and denials (“What were(was) you(I) to me(you)?”) all converge into one thing. This is when the loss loses its subject: the other.

Perhaps today, the concept of “loss” is being denied. In this era of seamless access (who can pronounce a complete severance from both on/offline world?), the gap between life and death becomes ambiguous, and the irreversible finality becomes unimaginable. The deceased’s still active social media account is renewed with comments,[ii] while facial expressions and the voices of those who passed revived through AI replace the painful mourning process with an immediate shock.[iii] When the deficient ego instead of the lost other or the revival that overlooked finality fills in the images of today, condolences are hastily sealed, promising a later time.

Once more, let’s think of the historical iconography of the crying face. It is severance that is emphasized. The image of tears confirms an eternal closure of the silent other side, reminding those who “remain” here to become anew through – and only by – the “remains” of those who left. It is, in fact, a complete farewell: “What you no longer see, they look at. What you no longer hear, they listen to. The song you no longer sing, they burst into. The joy of simple things appears to them by the light of your sad memory. You are that black but intense glow, which, since the dying of your light, freshly illuminates the day that had become obscure to them.”[iv]…

How can we bear the weight of irreversible separations and elapsed time? Can we slow down and stop in front of an image and contemplate the density of the past, the significance of others, and our intrinsic vulnerability as the finite? Artificial Tears questions whether the contemporary, surrounded by images, has forgotten how to handle loss and sustain grief. Also, the exhibit is just about to witness the tension between escaping images and those in pursuit, imperishable beings and those forever gone, perpetual access and attempts to cut off, the infinite present and the time that has passed.

Above all, Artificial Tears reflects on the habit of marking time, the tradition of keeping traces of others, and the attitude of preparing for what is to come from the old, through art history. The exhibition observes how the eight participating artists each cope with loss and the past. In doing so, it shows images that confirm irrevocable separations, reflect others in today’s survival, and refuse the homogenization of sorrow.

TZUSOO presents a reproduction of her work, I’M ASHAMED TO HAVE GRADUATED HERE (2022), in this exhibition. It is a graduation project and a statement to protest the school’s discriminatory policy of increasing tuition to students from non-European Union (EU) countries while studying in Stuttgart. At the center of the artwork is a figure bursting out in tears. The protagonist of these exaggerated tears is the artist’s alter ego Aimy, a virtual influencer and accepting the autonomy or emergent properties of AI data generation, TZUSOO recognizes Aimy as a half-subject. In other words, TZUSOO is in this world, while Aimy is on the other side. When the artist and Aimy operate dually but simultaneously, TZUSOO’s attempt to intervene in this world via the other world seems to convey the symptoms of the era that has lost its finality. In this case, can the avatar that tries to intervene by redirecting towards the real world make the platitude “flooding tears” into reality? The water flow inside the image at last fills up the water tank of the space.

Jihoon Yang discovers the reversal (which perhaps has been very long-standing) of the relationship between reality and virtual/illusion in contemporary landscapes. The inserted sentence from Taken (2023), “Forest fires exist for photographs,” clearly suggests this. Like “forest fire prevention campaigns” that award “wildfire” photos taken within the relevant year or the ‘decisive moment’ from a breakdown or an explosion, the image that guarantees repetition using what should not have happened as a driving force spreads rampantly. Jihoon Yang points out the phenomenon that the image does not represent the devastation but rather facilitates it. In addition, in the current world where reality and images are entangled, it is ascertained whether the image of tragedy makes the image in general, be consumed into one landscape of a single reality. Furthermore, in the dox (2023) series, he plays with frames of images that become irrelevant to reality or the truth. In a window of one social media where videos are infinitely updated, it is easy to find content edited and duplicated with its screen display ratio subtly modified. This “screen ratio” adjustment is sort of a trick that allows the reproduced copy to be recognized differently from its original to avoid copyright and other issues that will arise when the original is uploaded as it is. What is more, if the angle of the frame is tilted, the black letterbox that serves as a blank reaches a point where it becomes triangular rather than its usual “box” form. The inflated and distorted letterbox boasts its volume.

Hiju Yoon approaches the connection between the world behind the screen and reality as an extension or a renewal, unlike Jihoon Yang, who comprehends them in an antagonistic relationship. Premiered at her solo exhibition last year, The Silly Healy Milky Show (2023) is about a narrator who has lost the meaning of life coming over to the virtual world, constructing a second life. The life one has lost might be the disbanding of a band one adores, work overload (“died of overwork”), “suicide (d against one’s will),” or a deadline by 5th of November, 2022[v]. For whatever reason, those who have crossed over to this world type in their user ID for admission after selecting an avatar provided by the server and work in service for the suggested values. The new identity, “zizi,” runs through the empty world that shows no sign of vitality or reaction. Meanwhile, zizi detects that this place is built at a price amounting to the collapse of reality: “Aren’t you just trying to escape from the substantial server costs by exploiting the solidarity as an algorithm?” “Sharing becomes the currency used by the entities in itself,” “Does sharing symbolize humanity?” Despite doubting to pay the cost for the loss, she cannot stop cheering for those (who are gone in reality) revived here.

Moka Lee shows figures with tense pathos behind their somewhat unnatural smiles with the Surface Tension series. The artist recalls her childhood when she had to swallow the tears that were about to pour out and reflect them into the figure’s facial expression. The faces inside the paintings, which, in a way, resemble the artist, are usually found through social media. Moka Lee excavates poses and facial expressions that catch her eye from anonymous subjects within the network, purchases the portrait rights for the images, and uses them as motifs of her paintings. The point that the portrait models have no daily relationship with the artist, and there is no chance to meet in person during the production process, and so on, seems to ease the long-standing pressure of traditional portraiture of having to draw the subject in verisimilitude. Instead, with the work progressing without such a goal in the first place, the artist verifies the unilateral nature of self-projection the current relationship forming has. In other words, Lee’s figure paintings are identical images in which a single ego is projected. Keeping in mind the environment, where accepting others as they are, is completely prevented, the artist speculates the image of a face produced under such circumstances. Meanwhile, Moka Lee’s paintings as “contemporary portraits” also display a pictorial depth, as the paintings drawn in oil paints accumulated in thin layers propose the direction for penetration with moisture heading towards the inside instead of a smooth surface. Perhaps the tears here may overcome the “surface tension” of self-projection and allow the world of heterogeneity.

Moongi Gim presents Truth (2024), a large-scale sculpture that obstructs the center of the exhibition space. The sculpture reveals the fragility and triviality of paper, amplifying the unknown affect as a “total mass” while increasing its size weightlessly. Connecting paper up to the extent of filling a room and finishing it with adhesive tape, the artist uses traces that are impossible to regenerate and the arbitrariness of wrinkles that go above the artist’s intention as elements of sculpture. Truth, a rework of the preexisting work Jihye (2022), has new cracks created from covering up the original surface with paint, sparsely revealing the image/texts of Jihye under its surface. Interestingly, the sculpture contains small objects collected from daily lives (potato chips, lollipops, grandfather’s wristwatch, etc.) attached, which recalls a Benjaminian attachment, searching for “chiffre of wisdom”[vi] from old and trivial objects. The Tabasco series (2024) are recent works that maintain and embody the conceptual frame of “poor piece,” which Gim refers to his work as. Here, the artist emphasizes the meaning of the material more than usual. For example, self-adhesive paper, generally known as Post-it, holds a special meaning to contemporary Korean society, like its brand slogan “As much as you stick it, it is done.” It can be used during a pilgrimage of public space that displays photos of one’s “bias”[vii], honoring a sacrifice “that could have been me,” or taking part in accusing social irregularities. The artist accumulates Post-its layer by layer, creating a figure, fixing it with an instant glue “that holds the moment,” transforming possible meanings into a firm sculpture.

Suyon Huh‘s works exude thick lyricism with the materiality of the rough surface. Along with it, symbolic iconographies and ready-made carry specific meanings. First of all, the artist makes paper porridge by ripping page by page of the stacked fashion magazines delivered monthly to her home with her hands and soaking them in water. Then, the porridge is thickly applied to flat supports or found objects. As the mushed paper loses moisture and congeals combined with pigments, prominent uneven bumps evoke the paradox of “three-dimensionality of the surface” with the soggy liquidity of cured solids. By applying the expressive effect of the physical property of the material, the artwork slowly generates meaning, and Huh contemplates and makes images that operate the other way while paying close attention to the current state where the demand for highly stimulating/highly effective images, and consumerism outruns human values. In this exhibition, the artist reveals the intention for a narrative more directly through The Silent Scream of Inexplicable Despair (2024) and As if knowing nothing or as if unaware (2024). As if knowing nothing… (2024) features a character and dramatizes the story of someone who is forced to face one’s own tragedy as a subject within an edited frame, into a glass box. The audience is put to view the prescribed death of another, which has become consumer goods, and the recorded scene of death in advance simultaneously. In The Silent Scream…(2024) The artist shapes the sadness that passes through as well as goes beyond language (or symbols) into an image of an inverted umbrella.

Yoon hee Choi shows the landscape of time in The Land Before (course 1). The painting depicts the wall of the trail the artist walks by every day throughout the year, but it does not represent (in a traditional sense) the specific site or its surroundings. The artist told me that she puts more value in “the ordinary” than the newness (caused by physical changes in time and space), and it is not a coincidence that her paintings unfold and capture time of such everydayness – that leaves traces in repetitions. Often, when painting is called a medium that records time, it points towards its physical condition of chronologically accumulating pigments on a flat support. But to say time and the landscape of time in Yoon hee Choi’s paintings, one should not think of a laminated structure that adds surface upon a surface. Of course, the artist places a figure on the large, wall-like canvas and, at times, with texts and words from time to time, covering them with something else, and at that moment, the drawing penetrates inside even before the layer of the image has gained density. To absorb the paint into the cloth, Choi used a towel, a large brush, or even her hands to push it in, sinking something that went past the surface inwards. The screen looks transparent because the pigment sunk in instead of layering onto the surface. The same goes for why the screen seems as if it is foggy. Such pictorial expression, where the physical reality seems to have evaporated, conversely holds the elapsed time in the painting.

Sejin Park has constantly been studying landscapes. The landscape, here, refers to holding “a different life” that only appears during the drawing process, which is also a form of preserved memory. This means the landscape paintings by Sejin Park confirm that a place from the past is “irreversible outside (of) the painting” and that it is a “painted landscape” that is inseparable from the artist herself, despite the paintings indicating a specific site. This exhibition introduces big screen (2024), part of the series Summer, You which has been in progress since 2020, about a place on a summer’s day where nothing happened, let alone anything special. However, one noteworthy thing is that it rained there the whole day. Staying in a remote residence located at Wonju in Gangwon Province, where even lampposts are scarce, the artist observed the change in the landscape outside the window, where nothing could be seen with the pitch-black darkness at night. One day, during a sudden downpour on a steaming hot day, Sejin Park remembers the wet path reflecting a dim light, revealing its surroundings. Summer, You reconstructs in reverse chronological order the night when the artist (finally) saw a passerby, the evening just before the pouring rain, and the afternoon she ran barefoot down the asphalt road. Amongst the series, big screen depicts the afternoon and is also the painting that brought back the artist who had stopped drawing for a while after the first announcement of the series in 2020. Through the period when the artist was “still at a loss with what to do with the finite life,” she now attempts to paint once more, connecting herself with the place that bears the past and remains in the present painting.[viii]

Hojeong Hur

ENG translation by Yerim Lee

[i] Here are the following paintings that came into my mind. Portraits of women whose tears evoke strong emotions regardless of their authenticity or legitimacy: The Descent from the Cross (1435, Rogier van der Weyden), The Isenheim Altarpiece (1512, Matthias Grünewald), Penitent Magdalene (1550, Titian), Glass Tears (1932, Man Ray), The Weeping Woman (1937, Picasso), Crying Girl (1964, Roy Lichtenstein), 〈Untitled Film Still #27〉(1979, Cindy Sherman)….

[ii] “It’s been too long without seeing you.” […]”I hope ur … with me today!” […] “How much of this talking to Katie is self-gratifying, a performance: of cutesy, naive disregard for the finality of her death? A not-swallowing of its irreversibleness…” Tumarkin, M. (2018). Axiomatic. Transit Books. p. 29

[iii] Reviving the Voice of the Deceased Family Member… the Controversial New Feature of Amazon AI Voice Cloning. (2022, June 24). Yonhap News. Retrieved from https://www.yna.co.kr/view/MYH20220624014100704

Han, J. H. (2023, July 6). “Mom, I Have Missed You.” the Late Pilot Revived Using AI Technology. The JoongAng. Retrieved from https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/25175173

Jin, H.H. (2024, February 11). Lunar New Year’s Special VR Documentary I Met You 4 …I’m Meeting My 16-Year-Old Son, Who Died at 13. Maeil Business News Korea. Retrieved from https://www.mk.co.kr/news/hot-issues/10940518

[iv] Édouard Levé (2011). Suicide. Dalkey Archive Press. p. 13

[v] Itaewon Crushing: Condolence Visits Continue on the Last Day of the National Mouring Period. (2022, November 5). BBC News Korea. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/korean/news-63524957).

[vi] Buck-Morss, S. (1989). The dialects of seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. MIT Press. p.170

[vii] A term used by K-pop fans, ‘bias’ refers to one’s favorite member within an idol group.

[viii] Unless cited otherwise, all sentences with double quotations (“,”) are quotes from each artist.

– Download

– epilogue. 김유림 ,「눈물이라는 이름의 장소」.pdf