《인저리 타임 Injury Time》

2021.2.24. – 4.17.

강재원, 곽인탄, 오은, 이충현, 최태훈

기획/ 글 : 권혁규

그래픽 디자인 : 윤현학

주최: 뮤지엄헤드

《Injury Time》

Jaewon Kang, Intan Kwak, Eun Oh, Choonghyun Lee, Taehoon Choi

24.FEB.- 17.APR.2021.

Text / Curating : Hyukgue Kwon

Graphic Design : Ted Hyunhak Yoon

Hosted by Museumhead

이 글은 미래를 선행한 과거의 글 「인저리 타임」[1]을 꺼내 재구성한 후 같은 제목의 전시에 이어 붙인 것이다. 종료되지 않는 과거를 현재의 시공에서 결정하고, 이미 지난 무언가가 역전되는 상상을 하며.

‘인저리 타임’은 스포츠, 주로 축구 경기에서 선수의 부상(injury) 등으로 지연된 시간이 정규시간 이후에 더해지는 ‘추가시간’을 의미한다. 전시는 오늘 조각이 일종의 추가시간에 위치한다고 가정하며 그것이 어떤 부상을 축적, 극복하는지 또 어떻게 현재를 생성, 역전하는지 질문한다. 서구미술을 통해 새로움을 모색하고, 다시 그것의 토착화를 실험한 한국 근현대미술의 장면들은 오늘 작가들에게 회복 불가능한 부상으로 다가올까. 아니면 혼종성의 시간을 축적한 유의미한 성취로, 꽉 막힌 현재에서 돌파구를 찾는 가능성의 현시로 다가올까. 나혜석과 구메 게이치로, 구본웅과 사토미 가츠조, 권진규와 시미즈 다카시 작업에서 발견되는 친연성은 과연 치욕적인가. 김복진의 <여인의 입상>(1924)이 로댕의 <이브>(1881)를 본뜨고 최만린의 <이브>(1958)가 제르맨 리시에(Germaine Richier)의 작업을 참고했다고 하면, 이들이 두드린 조각의 근대적 돌파와 시대적 표상은 모두 무효가 되는 것일까.

《인저리 타임》은 특정 역사를 비집고 나온 물리적 실재로서 동시대 조각을 바라보고 이들이 과거와 어떤 관계를 맺고 있는지, 또 그로부터 어떤 어긋남을 생성하고 있는지 질문한다. 그렇게 오늘을 언젠가의 부상 혹은 엄살이 만들어 낸 혼종성과 양가성의 ‘추가시간’으로 정의하고, 무슨 일이 일어나도 이상하지 않은 시공에서 발현되는 반전과 역전의 시도로 당대 조각을 제시해본다.

전시는 오늘 조각에서 목격되는 복제와 전유의 방법론을 출발지로 삼는다. 참여작가 강재원, 곽인탄, 오은, 이충현, 최태훈은 각기 다른 방식으로 과거의 조각을 경유해왔다. 이들은 지난 미술의 실험을 현재와 결부시키고, 익숙한 미술의 개념으로 제품과 작품의 경계를 가로지른다. 또 역사적 장면과 현재의 기술을 연동시키고 과거를 뒤섞어 새로운 조각의 형태와 구조, 질감을 탐구해왔다. 《인저리 타임》에서 이들은 자신의 작업을 일종의 역사로 마주한다. 그리고 그 역사로부터 다시 한번 거리를, 시차를 만들어 낸다. 자신의 이전 작업을 신체 삼아 그동안의 실험을 또 다른 지평에서 발견하고 더 멀리 밀어붙여보는 것이다. 과거를 참조하고 전유한 작가들의 작업은 전시에서 시간의 피상적 상징물이 아니라 부동의 현재-미술에 추동력을 가하는, 아직 끝나지 않은 시공의 연쇄를 그리는 근거로 존재한다.

전시에서 작가들은 과거 조각의 무엇을, 어디로 이접하고 있을까. 이들은 자신의 일부가 되는 과거를 반성적, 비판적으로 재고하며 당대 조각에 어떤 문제적 장면을 만들고 있을까. 강재원은 3D 프로그램으로 기본 입체도형을 구성, 변형하며 조각의 형상과 제작 방식의 미래를 당겨본다. 작가는 구체적인 개념과 형태를 설정하고 그에 맞게 작품을 제작하는 대신, 컴퓨터 프로그램 상에서 기본 값으로 주어진 형태를 왜곡하고(Skew), 비틀고(Twist), 구부리며(Bend), 하중을 가하는(Gravity) 등의 효과를 적용하여 전반적인 조각의 토대를 구성한다. 이번 전시에 포함된 <Exo2_crop>(2021)은 그렇게 구성된 과거의 작업을 크롭해 크기를 키우고 각도를 비튼 결과물이다. 다시 말해, 거울처럼 주변을 반사하는 거대한 풍선 조각은 컴퓨터 프로그램으로 언제든 복제, 저장할 수 있는 형태를 삼차원의 공간에 출력한 결과인 것이다. 공기주입장치의 도움을 받는 얇은 막의 덩어리는 홀로 존재하지도 결코 유일하지도 않은 물질로 과거와 미래를, 평면과 디지털 세계를 오간다. 작업은 다시 3D 프린팅, 주물, 공기주입식 소재(inflatable) 등 여러 형태와 크기로 구현되며 동시대 조각이 삼차원의 물질, 볼륨, 질감에 품는 의혹을 팽창시킨다.

곽인탄은 머릿속을 떠나지 않는 파편들을 모아 조각적 형태를 구성하는 시도로 자신의 작업을 설명한다. 강박을 마주하는 과정과 유비되는 작업은 목적지를 알 수 없는 이어달리기처럼 몇몇 형태와 질감을 중첩, 반복하는데 이는 작가가 미술사에 등장하는 회화, 조각의 도판 이미지를 참조해 나름의 형태와 구조, 질감으로 재구성한 결과이기도 하다. 이번 전시의 <동세 21-1>(2021)은 지난 개인전에 선보인 <강박의 통제 불가능성>(2020)과 <지옥문 위에 앉아있는 사람>(2020) 속 인물을 해방시켜 어딘가로 빠르게 이동시키는 상상에서 출발한다. 이번에도 작업을 위한 여러 레퍼런스들이 준비되지만 이전보다 자유롭게 촉각적인 질감에, 형태의 파괴와 구축에 몰입한다. 그리고 여러 미술을 참조했던 자신의 이전 작업 <Unique Forms-1>(2019), <Gate-1>(2019) 등을 등장시키며 레퍼런스의 외적 수용이 아닌 그것을 관통한 작업의 내적 필연성을 나타낸다. <동세 21-1>은 과거의 단순한 잔여물, 소비적 조립이 아닌 여전히 새로운 충돌과 이동을 열망하는 형태로 등장한다.

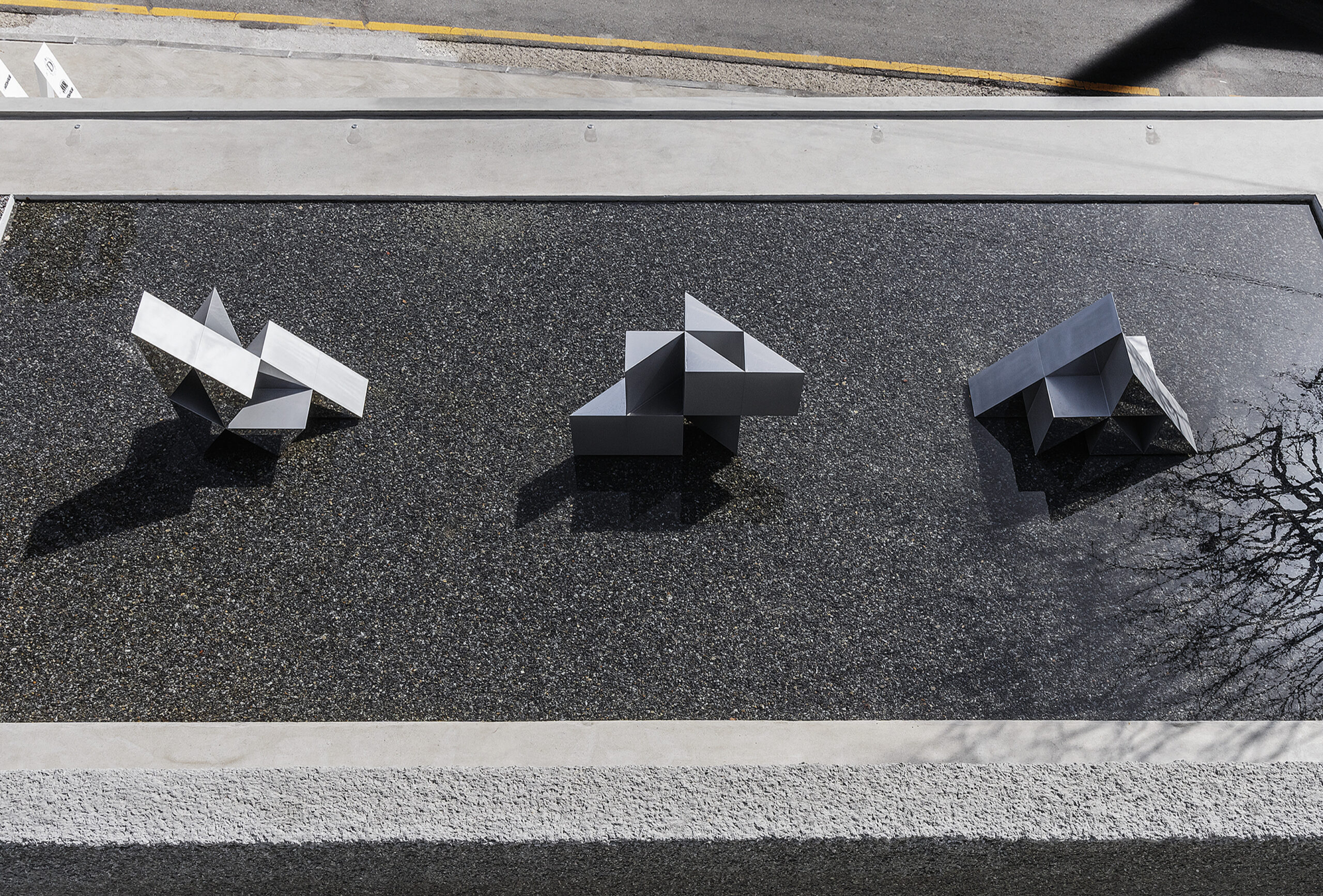

이충현은 지난 개인전에서 컴퓨터 프로그램 속 입체와 미니멀리즘 조각을 병치시키며 허구적 물질로서 전시와 조각을 경험하는 역설적 장면을 연출했다. 허구와 실제, 평면과 입체를 양분하지 않는, 하지만 분명한 낙차를 드러낸 작업은 이번 전시에서 야외 앞마당으로 그 무대를 이동시킨다. 컴퓨터 프로그램 상의 입방체를 정해진 규칙에 따라 기하학적으로 재구성한 듯한 <Trinity>(2021)는 흔히 볼 수 있는 미니멀리즘 조각을 단순 변형한 것으로 보이지만, 궁극적으로는 스크린 상의 평면-입체와 미니멀리즘의 병존이 아닌 보다 분명한 지각적, 경험적 물질의 생성을 추구한다. 스크린과 미니멀리즘의 정면성과 평면성은 실제 작업에서 사선과 반측면으로, 각기 다른 질감과 색감, 동세로 대체된다. 같은 조각 세 개를 다른 형태로 나란히 놓는 행위는 반복성과 연극성의 역사적 사례들을 호출하고, 이는 다시 작업이 포개 놓는 혹은 고의적으로 충돌시키는 복제 가능한 스크린과 광장, 소비적 장식품과 공공조형물에 대한 논의로 편입된다. 이 모든 것은 허위로서의 입체가 실제 공간에 침투, 교환, 경험될 때, 그리고 선행한 과정이 다시 역행할 때 분명해진다.

오은은 얼핏 단절된 것으로 여겨지는 한국 구상조각과 그것의 기념비성을 현재의 맥락에서 다시 헤아려본다. 그는 구상조각을 전승이나 역사화의 차원으로 접근하지 않고, 자기 주변의 상황을 압축적으로 결합시킨 연출 방식에 주목하며 주어진 상황, 재난, 부상을 극복하고 갱신하는 시도 자체를 기념한다. 이 같은 맥락에서, 작가는 손흥민과 부상당한 신체의 형상을 현재의 한계를 이겨내는 몸짓으로 제시한다. 그리고 늘 그래왔듯 한국 미술의 몇몇 장면을 겹쳐 놓는다. 일례로 <마이너 인저리>(2021)라는 작품의 타이틀은 박이소의 ‘마이너 인저리’를 호명해내고 타자성과 소수자성, 대안성에 대한 논의를 오늘의 상황에서 환기시킨다. 또 <마이너 인저리>와 <라스트미닛골>(2021)에서 확인되는 불구의 짓눌리고 종속된, 또 파편화된 신체는 1980년대 (신)형상 조각, 특히 류인의 작업을 떠올리게 한다. 줄곧 이전 미술을 참조해 온 작가는 이번 전시를 통해 한국미술의 현재를, 아직 정리되지 않은 미술의 성취를, ‘극장골’ 같은 개인의 약진을 그려본다.

최태훈은 기성품과 조각의 기능, 위상을 뒤섞으며 그것에 함의된 사회 역사적 맥락을 문제 삼거나 무효화하는 조각을 만들어왔다. 2018년부터 진행된 세 번의 개인전을 통해 DIY 제품의 기본 유닛들을 자의적으로 재구성하는 일종의 해킹 조각을 선보였고, 최근 윤민화 기획자와의 2인전 《트랙터》(2020)에서는 규격화된 사물과 신체(마네킹) 간 발현되는 긴장과 에너지를 상연하는 조각을 연출했다. 이번 전시에서 작가는 앞서 언급한 2인전과 2020년 개인전 《자소상》의 상이한 조형 방식을 하나의 작업으로 소환해낸다. DIY 가구 유닛들이 새로운 방식에 따라 수직 수평으로 연결되며 나름의 형태를 갖는 과정에 규격화된 사물에 긴장을 부여하는 신체와 스프레이 채색이 뒤섞이는 것이다. 대리석과 흙으로부터 생명을 끌어내던 조각은 마네킹으로 가뿐하게 대체되고, 전체 형태를 받치거나 연결하는 기성 오브제와 같은 역할을 수행하게 된다. 오브제-마네킹의 다이내믹한 포즈는 영원불멸의 신체와는 거리가 먼 동시대 물질과 문화, 행위의 모방을 재확인시킨다.

《인저리 타임》은 일견 분리된 것으로 여겨지는 두 세계를 교차시키며, 과거와 연동하고 또 이산하는 매체로 오늘의 조각을 바라본다. 전시에서 작품은 어제와 오늘, 평면과 입체, 기억과 경험, 복제와 창작을 겹쳐 놓기도, 이 모든 것을 허술한 실존의 기념비처럼 제시하기도 한다. 공적이고 역사적이라기보다 언제든 복사와 붙여넣기, 크롭과 재구성이 가능한 사적이고 탈역사적인 조각은 스스로 상이함을 직조하며 다양한 조건과 심리가 혼재하는 상태를 만들어 낸다. 다섯 작가들이 시도하는 과거의 탐닉은 박제된 시간과 역사의 재연이 아니라 그것을 마주한 현재 자체를 체화하고 무대화한다. 과거의 사실을 종합하지도 기념비를 세우지도 않으며, 오늘에 편재하는 시차와 끊임없이 나타나는 갈등을 공개한다. 이들에게 과거는 이어달리기의 대상도 통제나 망각의 시공도 아닌 끊임없이 출현하는 어긋난 현재이다. 이번 전시에서 포착해야 할 부분 역시 이런 반작용과 운동성이 아닐까. 작업이 특정 대상, 시공으로부터 어떻게 어긋나고 있는지 그 위배의 움직임은 어디서 어떤 현재적 성좌를 구성하고 있는지 계속 발견해야 할 것이다. 전시가 말하는 추가시간은 시작도 끝도 없는 뫼비우스의 띠가 아니다. 그것은 어긋남을 생성해내는, 돌파의 구멍을 만들어내는 나선형의 시공이다.

기획/글 권혁규

[1] 위에 언급한 글은 『계간 시청각』 4호의 크리틱 섹션에 게재되었다. 권혁규, “인저리 타임”, 『계간 시청각』 (No. 4), 2020, pp. 81-88.

Injury Time

The following introduction is a modified version of Injury Time1, based on which this exhibition was entitled. Here’s to imagining a world in which a not-yet-finished past determines the spatio-temporality of the present, and things that have already happened can be reversed.

(1. The above-mentioned article was published in the Critiques section of Audio Visual Pavilion Lab (No. 4). Kwon Hyukgue, “Injury Time,” Audio Visual Pavilion Lab (No. 4), 2020, pp. 81-88.)

Injury time is a sport term that is a synonym for “additional time:” in soccer, it refers to the same amount of time taken up to address an athlete’s injury being added after the official game time has been depleted. This exhibition, based on the premise that contemporary sculpture is poised on the brink of an “injury time,” questions which injuries this time was given in return for and how the extra time can be used for a productive purpose (or to reverse the current situation). Is contemporary Korean art, which explored new options through the medium of Western art and then experimented with “re-Koreanizing” such Western influences, an irreversible injury for artists today? Or, has such experimentation produced meaningful outcomes that will help artists of the 21st century to find a way out of their trapped-in state? Are the similarities between the artworks of (Korean and Japanese artists) Na Haesuck and Kume Keiichiro, Gu Bonung and Satomi Katsuzo, or Kwon Jinkyu and Shimizu Takashi disgraceful? If Kim Bokjin’s Standing Woman (女人立像) (1924) was modeled on Auguste Rodin’s Eve (1881), and Choi Manlin’s Eve (1958) referenced the works of Germaine Richier, are the Western-influenced Korean elements of Kim and Choi’s work invalid?

Injury Time observes contemporary sculpture as the physical traces of a particular historical period and questions the type of relationship that these sculptures have with the past as well as the inconsistencies that occur from this relationship. It defines “extra time” as the hybridity and ambivalence of today that was created by an injury (or exaggerated sense of injury) from the past and suggests a new role for sculpture as agents of reversal in a spatio-temporal environment in which nothing is off limits anymore.

The exhibition begins from the methodologies of replication and exclusive ownership that are found in contemporary sculpture. Kang Jaewon, Kwak Intan, Oh Eun, Lee Choonghyun, and Choi Taehoon have, each in their own way, journeyed through (and accepted elements of) previous genres/schools of sculpture. They apply artistic experiments of the past to the present and toe the line that divides art and commercial product through familiar artistic concepts. They also link historic incidents with contemporary technologies to explore new sculptural formats, structures and textures. In Injury Time, the artists come face-to-face with their creations as if with history itself, and distance themselves once more from this history. They use their previous work as the basis for rediscovering their experiments in a new realm and pushing back the boundaries of these experiments even further. The creations of these five artists, for whom the past is both a reference point and object of exclusive ownership, are displayed within this exhibition not as the passive symbols of time. Rather, they exist as representative of the key to grasping a still-ongoing time/space that serves as an impetus for the fixed, immobile relationship between art and the current age.

What aspects of previous schools of sculpture are the artists using? Where are they applying these aspects to? By being apologetic or critical toward the past, which makes up (a part) of them, how are they bringing up the problematic aspects of past sculpture into the present? Kang Jaewon uses a 3D program to create and edit three-dimensional shapes, suggesting that this is how sculptures may come to be produced in the future. Rather than first coming up with a concept and format and then shaping the artwork based on these, Kang establishes the foundations of the sculpture via computer program by skewing, twisting, bending, and applying gravity to the shape created by entering a few default values. Exo2_crop (2021), which is featured in this exhibition, is the outcome of using a computer program to crop, enlarge, and skew the angles of parts of past sculptures. In other words, the massive balloon-like sculpture whose color makes it look like a giant mirror, is the three-dimensional print-out of a shape that can be replicated or saved any time via computer program. The thin membrane, which is assisted by an air pump, is a material that is neither independent nor unique but can go back and forth between past and future as well as two-dimensionality and the digital. Kang’s creations, by taking on diverse formats and sizes (e.g., 3D printing, metal casting, inflatable material), give voice to the doubts harbored by contemporary sculpture about three-dimensional material, volume, and texture.

Kwak Intan explains his work as “an attempt to gather together fragments that refused to leave my brain and turn them into a sculptural format.” His creative process, which is compared to the process of coming face-to-face with obsessive compulsion, is like a relay race whose destination is unknown, in that it overlaps/repeats several shapes and textures. This is also the outcome of Kwak’s referencing of plate images of paintings and sculptures and re-purposing what he learned into new shapes, formats and textures. Movement 21-1 (2021) begins from the artist imagining that he has set the subject of The Out of Control of Compulsion (2020), which was featured at a recent solo exhibition, and Person sitting on gate to hell (2020) and is taking him somewhere very quickly. It, like Kwak’s previous creations, references multiple artworks. It is also, however, more focused than previous creations on a touch-inviting texture and the destruction and rebuilding of shape. By citing Unique Forms-1 (2019), Gate-1 (2019), and other previous creations, Kwak expresses the need not to accommodate references superficially but to create things that penetrate (and, eventually, come out at the end of) them. Movement 21-1 is not merely a remnant of the past or a passive rebuilding of it. Rather, its format suggests that the character is still very much interested in new conflicts and journeys.

In his most recent solo exhibition, Lee Choonghyun juxtaposed a 3D figure in a computer program with a minimalist sculpture, giving the visitor the paradoxical experience of the art exhibition and sculpture as fictional entities. The artwork for this exhibition, which is displayed in Museumhead’s outdoor area, has physical height but, at the same time, does not bisect the real from the fictional or 3D from 2D. Trinity (2021) looks like a geometric remodeling of three cubes from a computer program. It may seem to be a modification of a common minimalist format. Ultimately however it is not a simple juxtaposition of minimalism in 2D and 3D, it is the creation of a perceptual and experiential substance. The two-dimensionality and façade-emphasis of the screen and minimalism are replaced in Lee’s creative process with diagonal, half-sided pieces that each have a different texture, color, and movement. Placing three sculptures of the same style (but different shapes) in a row brings to mind historical events that are characterized by a repetitive or dramatic quality, which eventually leads back to discourse on the replicable screens, plaza, easily-consumed ornaments, and 3D installations/sculptures in public areas that are referenced (or intentionally brought together in conflict) by the artwork. All of these things are made very clear when a fictitious 3D object hurtles into, is replaced by something else in, experienced in a real space or vice versa.

Oh Eun explores the formative Korean sculpture, which seems all but discontinued in the current age, and its monumentality within a 21st century context. Oh approaches formative sculpture not from the perspective of tradition or historization but as something that can be combined with a condensed version of her personal experiences. In other words, it is the “commemorating of a commemorative act”—a repackaging of attempts to overcome a particular situation, disaster, or injury. It is in this way that the artist transforms Sohn Heung-min and the injured human body into bodily movements that overcome the limitations of one’s current circumstances. She also, as usual, includes a few moments of Korean art history. Minor Injury (2021) refers to Bahc Yiso’s gallery space of the same title, directing our attention current discourses on othering, what it means to be a minority, and solutions/means of addressing the needs of such groups. The body that has been segmented or enslaved to disability that appears in Minor Injury and Last Minute Goal (2021) brings to mind the human sculptures made in the 1980s by Ryu In. Oh, who has studied art history extensively, shows us the status of Korean art today, the as-yet unorganized accomplishments of Korean art, and her increasing visibility as an artist that very much resembles a last-minute goal.

Choi Taehoon blends commercial products with sculpture’s functions and cultural status to create artworks that critique or invalidate the sociohistorical context they are based on. His three solo exhibitions, which have been held since 2018, featured creative reconfigurations of the components of DIY products. In Tractor (2020), through which he was featured alongside curator Yoon Min-hwa, Choi presented sculptures on the tension and energy that exists between standardized objects and bodies (mannequins). For this exhibition, Choi blends two disparate styles: the one from Tractor and the one that pervades Self-portrait, a solo exhibition held in 2020. DIY furniture parts are joined together horizontally and vertically in unconventional ways and the standardized wooden pieces are imbued with a tense energy by draping them with spray paint and body parts or clothing. The sculpture, which drew life from clay and marble, is easily replaced with a mannequin, which ends up playing the same role as the objects that are usually used to connect or prop up a structure. The object-mannequins make us think about contemporary materials, culture, and the imitations of movement—all of which are not at all related to the idea of an “eternal body.”

By juxtaposing two seemingly disparate worlds, Injury Time spotlights contemporary sculpture as a medium that can be linked to or severed from the past. The artworks in this exhibition overlap past and present, 2D and 3D, memory and experience, and replication and creation. It often presents all of these things as faulty statues of reality. Private and post-historical sculpture, which, rather than being public or historical in nature, can be replicated, copy-pasted, cropped or reconfigured at any time. In this way, such works are declared as unique entities and achieve a mixture of diverse psychological states and conditions. The five artists’ attempts to explore the past do not end with lifeless reenactments of time or history: rather, they take on the qualities of and showcase the current age as an onlooker of the past. They do not attempt to build monuments to or try to write a full report of past truths. Instead, they draw our attention to the endless conflict that history brings about in its time difference with today. For the artists, the past is not a relay race or a spatio-temporal entity of control or oblivion: it is our constantly-intervening, discordant present. This is perhaps the point that this exhibition strives most to portray. We too will have to keep striving to discover how art is discrepant from a particular subject or time/space and where and how such discordance is enacted in our present. The extra time that this exhibition has done its best to embody is not a Mobius strip. It is a helical space/time that produces discrepancy as well as spaces through which we can escape from such limitations.

Kwon Hyukgue