* 황재민 비평가의 리뷰 「두 번: 반복되어야 하는 반복」(2024)은 NEWS 탭에서 다운로드 하실 수 있습니다.

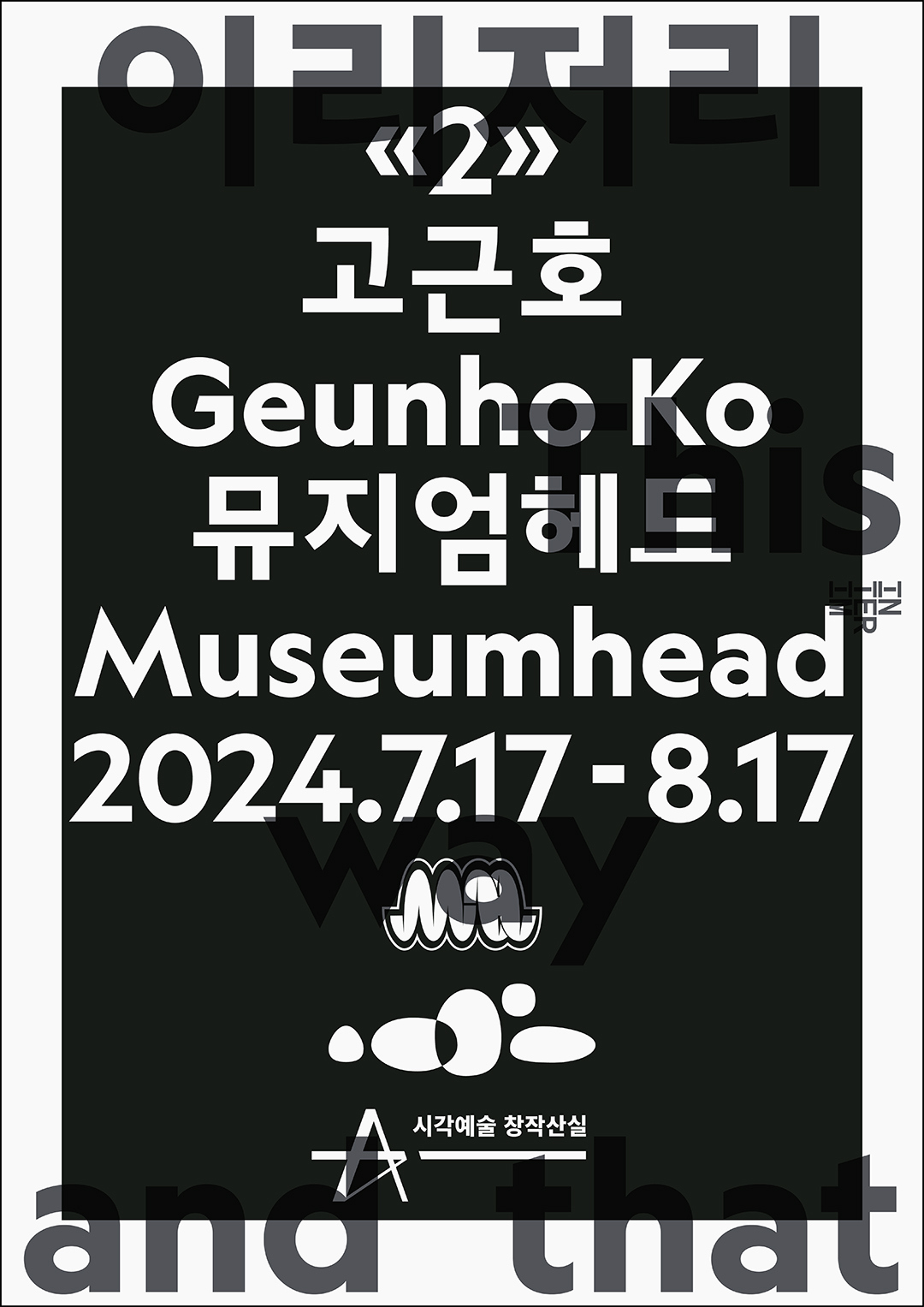

고근호 개인전 《2》

2024.07.17.-08.17.

12:00-19:00 (일, 월 휴관)

서울시 종로구 계동길 84-3, 1층 뮤지엄헤드

기획: 권혁규

그래픽 디자인: A Studio A (이재환)

주최, 주관: 뮤지엄헤드

후원: 한국문화예술위원회, 2024년 시각예술창작산실

2

Geunho Ko Solo Exhibition

2024.07.17.-08.17.

12:00-19:00 (closed on Sun, Mon)

Museumhead, 1F 84-3, Gyedong-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul

Curated by Hyukgue Kwon

Graphic Design by A Studio A

Hosted and Organised by Museumhead

Supported by Arts Council Korea, 2024 ARKO Selection Visual Art

다시, 게임을 시작하자.

칸 채우기, 삼각형, 궤적 그리기, 다시 그리기, 종이 뿌리기

게임 참여를 위해 당신이 알아야 할 모든 것이다.

고근호 개인전 《2》를 기획하며 다음을 첫 문장으로 적는다. “같은 전시를 다시 만드는 일은 가능한가”, “그건 어떤 의미를 갖는가”. 보다시피 이 문장은 첫 번째 문장이 되지 못한다. 형식적으로도 내용적으로도 실패하고 만다. ‘다시 만들기’는 일종의 선험적 조건과 연속성을 전제한다. 그 행위에는 어떤 구조나 형태들이 이미 새겨져 있다. 그렇게 첫 문장이 되려는 ‘다시 만들기’는 특정 조건 안에, 괄호 안에 놓인다. (이런, 시작부터 꼬여버린 《2》의 시간.)

전시라는 매체는 애초에 반복을 허락하지 않는다. 전시는 제한된 시간과 공간 안에서 반복과 확장을 가로막는 통제의 메커니즘을 통해 발생하는지도 모른다. 단 한 번의 사건을 강령으로 삼으며 지각을 가설하고 교차하는, 또 그에 맞는 형태를 새기는 과정이 ‘전시 만들기’ 일지도 모른다. 시작과 함께 끝으로, 또 끝을 위해 시작으로 질주하는, 일종의 망각 장치로 전시 매체를 떠올려 본다. (잠깐, 전시 따위를 매체라 말하다니. 당신은 분명 전시기획자겠군. 이건 경멸의 언어가 분명하다.)

한번 거하게 치르고 끝나는 전시는 비난과 경멸의 대상이 되곤 한다. 망각으로 내달리는 사건은 (과)소비와 (슈퍼)마켓의 등가물로 인지되고, 불순한 태도와 회의론이 스며드는 장소가 된다. 비슷한 장면들, 공허한 말과 이미지를 내세운 전시들을 전지구적 현상처럼 목격한다. 그리고 그 광의의 현상에는 불완전한 동시에 일반적인, 또 보편적인 미술의 관념/형식들이 (예를 들면, 모더니즘, 추상회화 등이) 일종의 촉매제처럼 자리하곤 한다. 그럼 질문. 오늘 전시는 말뿐인 대역 노릇에서 벗어나 어떤 ‘단 하나의 사건’이 될 수 있는가. 그 사건은 불완전한 일반성의 개념을 망각과 소비의 지반에서 떼어내, 다른 시간성에 결속시킬 수 있을까. 전시의 시간성, 조금 거창하게는 역사성을 말할 때 동반되는 이 겸연쩍음은 정말 피해야만 할 일인가.

《2》는 고근호의 최근 개인전 《이리저리》(2024, 인터럼[1])를 다시 전시하려는 열망에서 시작한다. 그리고 그 열망은 작가의 또 다른 개인전 《조율하는 퍼즐》(2022, Hall1)로, 우연한 기회로 마주했던 다른 작업/장면들로 번진다. 여기서 ‘2’는 선행하는 무언가를 전제하는 상태, 확장 가능한 네트워크의 조건, 연속과 반복의 시공을 지시한다. 그렇게 지나간 사건/전시를 이동, 촉진시키는, 단순 (재)생산을 넘어 복수화와 확장의 시도로 이번 전시를 제시해본다.

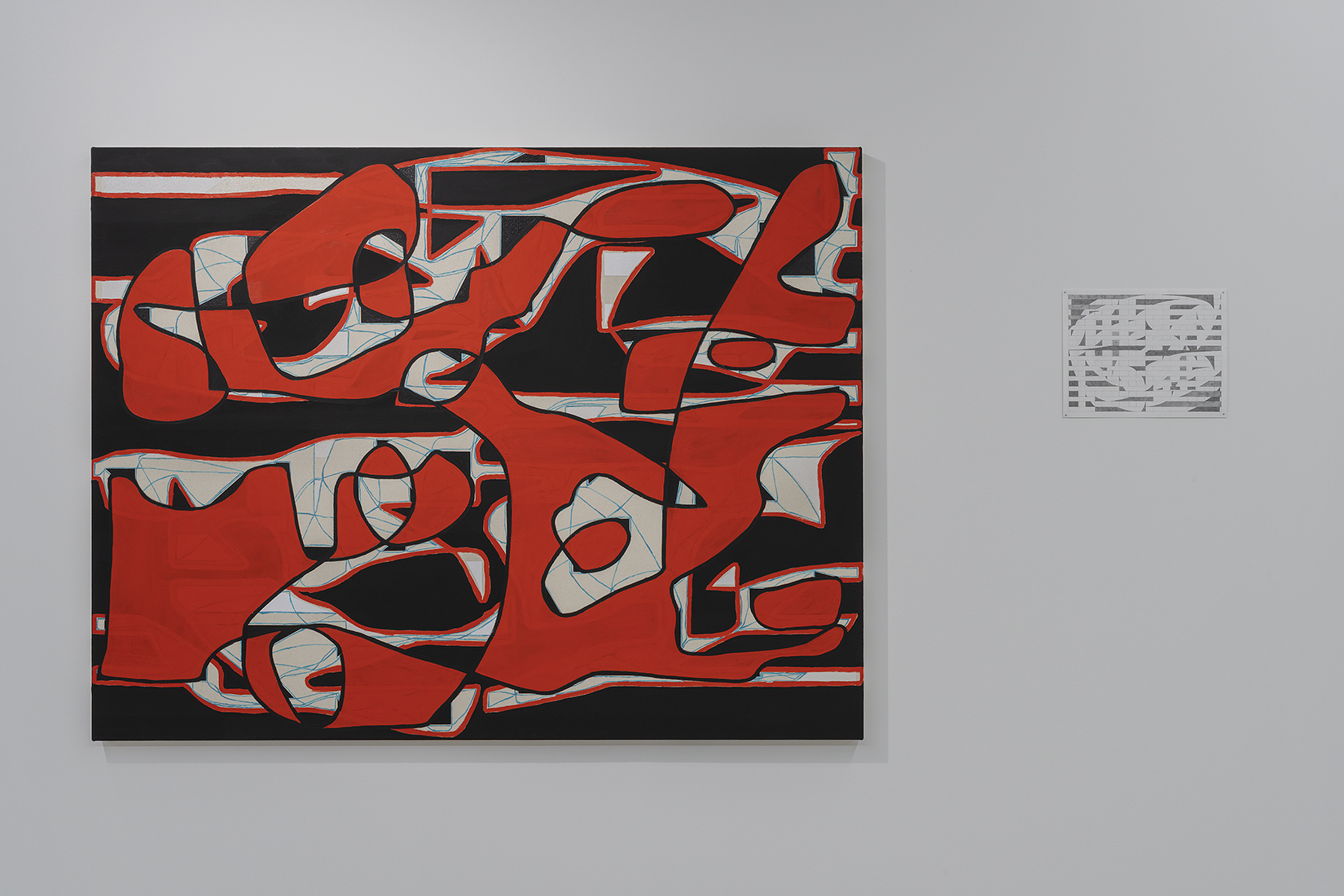

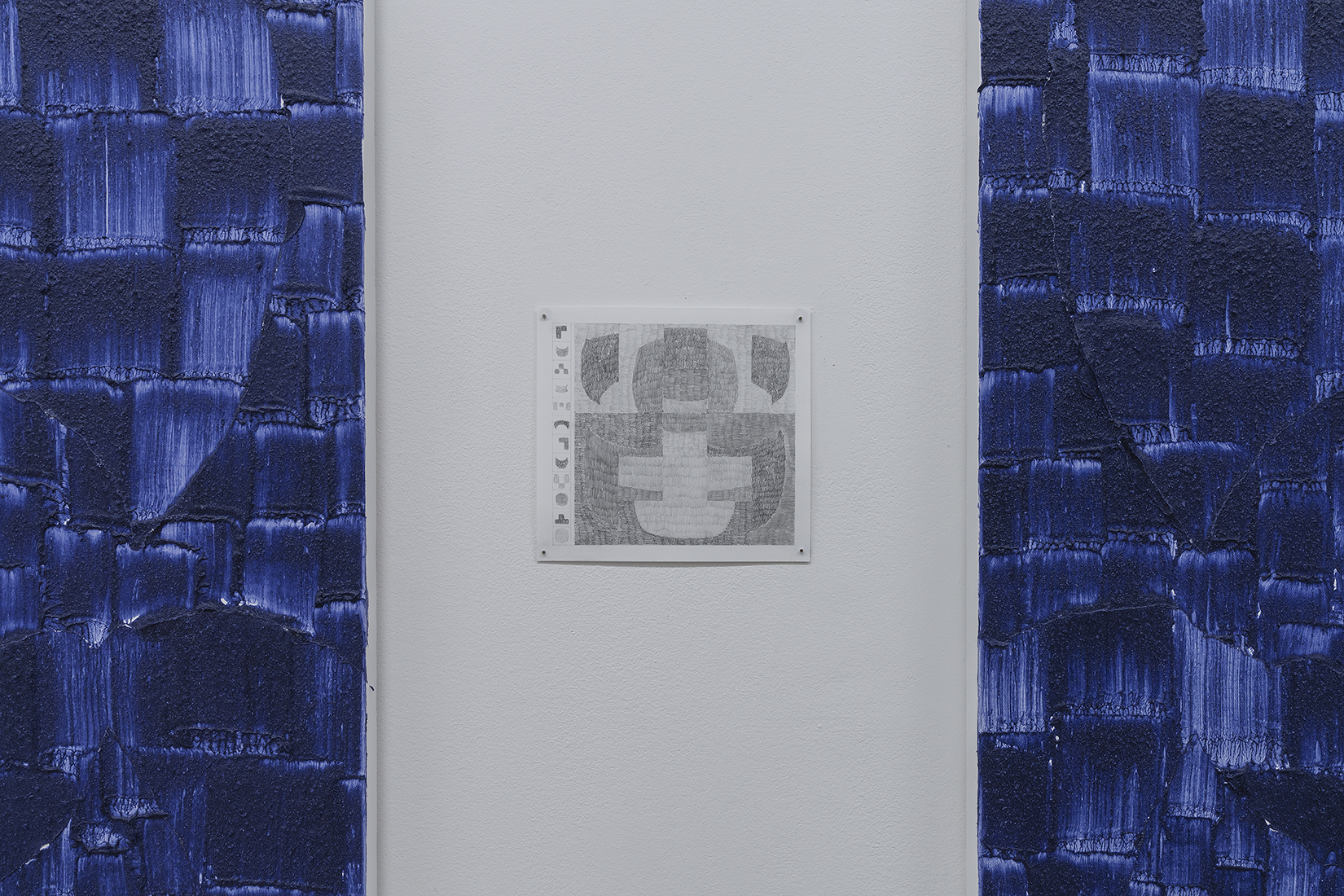

《2》는 고근호 회화의 방식/규칙을 방법론 삼아 구체화된다. 전시는 작가 작업에서 규칙의 이행이 이미지의 등가물처럼 자리한다는 점에 주목하고, 이미지 형성 방법이 추상회화의 구실을 마련해가는 과정을 구체적으로 확인, 공유한다. 다시 말해, 전시는 그 자체로 고근호 회화의 자가 증식으로, 3차원적 확장으로 이해될 수 있다. 다음은 증식의 요체가 되는 몇 가지 방법/규칙들이다. 1. 칸 채우기: 고근호는 미리 스케치한 (격자)칸을 채우며 회화를 제작한다. 각 칸은 하나의 사건으로 서로 연결되고 관계 맺는다. 애초에 크기가 다른, 균형이 맞지 않은 격자(들)의 틈으로부터 작가는 또 다른 균형의 여지를 발견하기도 한다. 2. 삼각형: 회화에 자주 등장하는 삼각형은 일종의 상황을 만들어낸다. 중심(없음)을 만들어내는 도구가 되기도, 방향을 지시해 주는 이정표나 피해 가야 할 장애물이 되어주기도, 조건(의 이행)을 확인, 상상하는 배경이 되기도 한다. 3. 궤적 그리기: 고근호는 자신이 구성한 조건 위에서 궤적을 그린다. 칸과 삼각형이 조건을 위한 요소라면 궤적은 조건 위에서의 (즉흥적이고 우발적인) ‘길 찾기’, ‘헤매기’를 기록하는 요소다. 작가는 화면에서 어떤 움직임을 상상하며 궤적을 쌓거나 깎아 나가기도, 궤적이 만들어내는 영역/자리에 색을 채워 넣기도 한다. 4. 다시 그리기: 작가는 유사한 그림을 다시 그린다. (당연히) 미리 세워둔 그리기의 계획은 늘 모호한 빈틈을 드러낸다. 작가는 이 빈틈을, 다시 그리기가 드러내는 차이의 파장을 능동적으로 상상하기도 한다.[2]

위 규칙들은 회화 발생의 조건이 된다. 규칙들은 그 자체로 칠해지고 그려진다. 체계적인 과정과 규칙에 따라 만들어지는 회화는, 자체적인 생성 논리를 갖는 디지털 코드처럼 보이기도 한다. 하지만 작업은 완전히 코드화되지 않는, 출발 지점에 있던 그 규칙으로는 해명되지 않는 이미지로 귀결된다. 작업 스스로 구조를 구축/해체해 나가며, 종국엔 ‘추상회화’가 가능해지는 것이다. 규칙을 완벽하게 수행할 수 없는 회화의 한 국면은 최근 개인전 《이리저리》에서 보다 또렷하게 나타난 듯하다. 수행 불가능성은 아이러니하게도 또 다른 이미지 생성 ‘방법’의 조직을 필수 조건으로 삼으며 (재)설정된다. 몇 가지 규칙을 실행하며 화면에 이정표를 만들고, 그 사이를 말 그대로 “이리저리” 오간 흔적의 층위를 펼쳐 놓았던 전시, 《이리저리》는 어쩌면 규칙의 벗어남을 또다시 방법-화하는 시도였는지도 모른다. 여기서 방법은 질서를 되풀이하는 행위라기보다는, 그것의 (이전의 비/규칙을 포함한) 회화적 전개를 가능케 할 ‘조합’, 혹은 ‘게임’에 더 가까워 보인다.

‘그림을 어떻게 읽을 것인가 How to read a painting?’라는 오래된 질문은,[3] 회화를 일종의 해독, 독해의 대상으로 설정한다. 그리고 그 시도는 이미지의 은유와 상징, 의미와 서사를 이해하는 데 더 집중해온 듯하다. 이번 전시는 그림 읽기를 ‘방법’을 향하도록 돌려세운다. 이미지를 알레고리적 서사와 개념으로 독해하는 방식에서 벗어나 그림 자체를, 그 정립의 구조를 읽어보도록 한다. 전시가 확장, 혹은 게임의 요체로 설정하는 ‘어떻게’는 회화사의 주요한 변곡점—회화의 목적이 ‘대상’의 재현에서 ‘추상’으로 이동하는 움직임—과도 밀접하게 연관된다. 대상에서 벗어난 ‘방법’은 매체의 독립성과 고유성을 확보할 뿐 아니라, 개념적으로 ‘추상’의 발생 논리를 정립하곤 했다. 대상을 전제하지 않는 고근호의 방법 역시 나름의 (비)과정을 거치며 추상-회화의 생성 게임을 지속한다. 《2》는 그 방법이미지의 추적을 제안해본다. 전시장에 증식하는 방법-이미지의 요체를 파악하며 고근호 회화를 연속된 과정, 확장된 시공에서 읽어보길 바란다.

《2》는 (실행 불가능한) 규칙과 (비정형적) 구성을 오가는 회화를 추적하기 위해 네트워크로의 진입을 안내한다. 흔히 말하는 스크린 속 가상성의 세계를 넘어 물리적 현존으로서의 회화/전시에, 게임에 동참하길 요청하는 것이다. 디지털 미디어와 스마트 폰의 분열적 시공, 알고리즘적 행동인식을 의태하는 동시에 모종의 탈주/오류를 시각화하는 듯한 회화의 생태계 안에서 마주한 현재를, 그것의 시각장을 ‘다시’ 감각해 보길 바란다.

미술에서 게임은 생소한 언어가 아니다. 비디오/웹/디지털 게임의 문법을 따르는 최근의 작업들부터 시간을 조금 더 당겨 플럭서스의 사례들까지. 변칙적 사고의 가능태, 시뮬레이션으로서의 게임은 구태의 예술을 재고한다. 조지 마키우나스(George Maciunas)는 “모든 체스 선수들은 예술가”[4]라 말했던 뒤샹의 주장을 따르며, “부르주아의 식상함과 지식인, 전문가와 상업화된 문화를 숙청하라. (…) 모방, 인위적인 미술, 추상미술, 재현미술을 숙청하라.”[5]고 말했고, 또 다른 플럭서스의 멤버 켄 프리드만(Ken Friedman)은 “패러다임 전환적 놀이”로 미술의 게임을 말했다. 급진성과 유희성을 강조하는 이들의 게임은, 회화에 견주자면 그 매체를 위해 기능했다기보다 거부하는 방식으로 진행되었다고 볼 수 있다.

그런데 고근호의 게임은 회화를 위해 기능하며, 회화로 마무리되는 구조를 성립하려 든다. 전시는 고근호의 ‘방법’이 회화 매체 자체와 그것을 조건 짓는 관습들을 일종의 레디메이드나 파운드 오브제로 간주하는 것은 아닌지 질문해본다. 나아가 회화를 이미 혼합된 매체(인터미디어), 불완전한 이미지로 설정함으로써 게임의 동력을 마련하고, 이를 또 다른 현실의 게임/네트워크로 확장되는 상황을 가설해본다. 여기서 누군가는 ‘추상회화’를 왜 구체적 특이성으로 다시 독해하려는 것인지, 그것이 내포하는 보편성의 개념을 왜 게임의 반(/비)미학적 논리로 갈음하려는 것인지 물을지도 모른다. 전시는 보편의 ‘불완전성’을 여전히 독해/번역의 대상으로 설정한다. 구체적 지점으로부터 보편에 다가가고 매체의 환유적 성질을 재고하며 오늘 추상회화/전시가 조금 다른 기능과 시간성에 위치하는 장면을 상상해본다.

《2》는 고근호의 회화를 과거-현재-미래, 이곳-저곳의 연속된 시공에 펼쳐 놓는다. 게임에 비유되었지만, 전시에는 일반적으로 게임을 정의하는 장애물이나 목표도, 절차와 경쟁도, 승자와 패자가 갈리는 승부도 없다.[6] 동시대 미술 자체가 우울한 ‘엔드 게임’에 비유될 때, 이번 전시는 과연 어떤 게임을 전개할 수 있을까. 실패를 전제한 종말 놀이로서의 게임이 아닌, ‘방법’과 ‘과정’의 변주, 확장으로서 또 다른 사건/전시를 열어 보일 수는 없을까. 그 가능성은 익숙한 일반성, 불완전한 보편성의 현재를 도약시키는 시도가 될 수 있을까. 심지어 그것이 전적으로 (회화/전시/미술 매체의) 내부에 있어왔다고 말해 볼 수 있을까. 게임을 시작하자. 필요한 단어들은 다음과 같다.

칸 채우기, 삼각형, 궤적 그리기, 다시 그리기, 종이 뿌리기

당신이 알아야 할 모든 것이다.

기획/ 글 권혁규

[1] 2023년 9월 문을 연 인터럼은 “세 작가의 공동 작업실 일부를 개조해서 만든 아티스트 런 스페이스”로, 고근호의 개인전을 비롯해 “세 번의 개인전과 두 번의 2인전, 그리고 단체전과 퍼포먼스 프로그램을” 운영하고 지난 7월 10일 종료를 알렸다.

[2] 해당 문단에 언급된 ‘몇 가지 방법/규칙들’에 대한 설명은 작가 노트를 인용, 참고.

[3] 일례로 미술사학자 에른스트 곰브리치(Ernst Gombrich)는 1961년 발표한 아티클 “How to read a painting – Adventures of the mind”에서 마우리츠 코르넬리스 에셔(Maurits Cornelis Escher)의 미로 같은 그림의 디테일을 분석하며 미술/이미지에는 눈에 보이는 것 이상의 의미가 있다고 설명한다.

[4] 베르나르 마르카데, 『마르셀 뒤샹: 현대미학의 창시자』, 고광식 외 역 (을유문화사, 2010) 참조.

[5] George Maciunas, Manifesto (1963, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection).

[6] Jesper Juul, Handmade Pixels: Independent Video Games and the Quest for Authenticity (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2019) 참조.

Again, let the game begin.

Fill in the blanks, Triangles, Trajectories, Repaint, and Scatter papers.

That’s all you need to know to join the game.

“Is it possible to re-make the same exhibition again? What does it mean?” While these questions might seem apt as the opening lines, they ultimately fail both formally and content-wise. The concept of “making an exhibition again” presupposes an a priori condition and its continuity, implying a pre-existing structure inherent in the act. The “re-making” mentioned in the initial sentence is thus confined within specific conditions, almost as if placed within parentheses. (Oh, the time of “2,” thwarted from the beginning.)

An exhibition as a medium does not allow for repetition. We can say that an exhibition occurs through a mechanism of control that prevents repetition and expansion within a limited time and space. The process of hypothesizing, intersecting perceptions, and shaping them into a form, using “a single” event as a guiding principle, may be called “exhibition making.” I think of the exhibition medium as a kind of oblivion device, racing to the end with the beginning, and to the beginning for the sake of the end. (Wait, you say “exhibition as a medium”? You must be a curator! – said with a pejorative tone.)

An exhibition, once opened with great acclaim and then concluded with nothing left behind, is often vilified and scorned. We witness similar scenes throughout exhibitions filled with empty words and images. Exhibitions that rush to oblivion are perceived as equivalent to (over)consumption and (super)markets, infiltrated by impure attitudes and skepticism. However, an exhibition still conveys imperfect yet universal artistic concepts and forms (e.g., modernism, abstract painting, etc.). This raises the question: Can today’s exhibition become a “singular” event that can lift values from the ground of oblivion and consumerism and bind them to a different temporality? Is this double entendre that accompanies the temporality of an exhibition—or, to put it more bluntly, its historicity—really something to be avoided?

《2》 begins with the desire to reexhibit Ko’s recent solo exhibition This Way and That (2024, Interim[1]), and extends to other works/scenes that the artist encountered by chance, such as another solo exhibition, Puzzle that Tunes (2022, Hall 1). The number “2” here refers to a condition that presupposes something that precedes it, a condition of an expandable network, a space-time of continuity and repetition. I present this exhibition as an attempt to move and facilitate past events/exhibitions, to pluralize and expand beyond mere (re)production.

《2》 adopts the methods and rules of Ko’s painting as its own methodology. The exhibition highlights the fact that the fulfillment of these rules is equivalent to an image in the artist’s work, concretely confirming and sharing the process by which the method of image formation provides the pretext for abstract painting. In other words, the exhibition is a self-reproduction of Ko’s paintings and can be understood as a three-dimensional extension of them. Here are some of the methods and rules used by the artist, which form the basis of the exhibition: 1. Fill in the blanks: Ko creates his paintings by filling in the pre-sketched (grided) blanks. Each square is connected and related to the others by a single event. From the gaps in the initially unbalanced grids of different sizes, the artist finds another space for balance. 2. Triangles: The triangle, which often appears in his paintings, creates various situations. It can serve as a tool for creating a center (or absence), a signpost for direction, an obstacle to be avoided, or a background against which conditions (fulfilment) are checked and imagined. 3. Trajectories: Ko draws a trajectory on the conditions he has constructed. If the squares and triangles are the elements of the conditions, the trajectory records the (improvised and accidental) “wayfinding” and “wandering” within those conditions. The artist imagines the movement on the canvas, building up or cutting away trajectories, and filling in the areas created by the trajectories with color. 4. Repaint: The artist redraws or repaints a completed work anew. The pre-drawn plan, following the rules of 1-3, always reveals the gaps between the plan and drawn/painted images. The artist actively imagines these gaps, exploring the ripples of difference that redrawing and repainting reveal.[2]

These rules are the conditions for painting to occur. They are painted and drawn on canvases. A painting created according to a systematic process and set of rules may seem like a digital code with its own generative logic. However, the work ultimately ends up as an image that is not fully codified and cannot be completely explained by the rules that were the starting point. The work builds and deconstructs its own structure, making “abstract painting” possible. This inability to perfectly follow the rules is particularly evident in Ko’s recent solo show, This Way and That. The impossibility of adhering to the rules is ironically reestablished as a necessary condition for the organization of another image-generating “method.” The exhibition, which enforced a few rules, created signposts on the canvas, and laid out layers of traces that literally go “this way and that,” was perhaps an attempt to methodologize the breaking of rules once again. Here, the method seems to be more of a combination or game that enables pictorial development (including the previous non-rules) rather than an act of repeating the order.

The age-old question of “How to read a painting?”[3] sets up painting as an object of reading or decoding, often focusing on understanding the metaphor, symbolism, meaning, and narrative of the image. This exhibition shifts the question of how to read a painting back towards the “how.” Instead of interpreting the images as allegorical narratives and concepts, viewers are invited to read the paintings themselves, examining the structure of their formulation. The “how” of the exhibition is closely linked to a major inflection point in the history of painting: the transition from representation to abstraction. By departing from subject matter, the method of painting has not only secured the independence and uniqueness of the medium but has also established the logic of the occurrence of the “abstract.” Geunho Ko’s method, which does not presuppose a subject, goes through its own (un)process and continues the game of generating abstract paintings. 《2》 proposes tracing this method and its generated images. By grasping the essence of the “method-image” that multiplies in the exhibition space, we hope to read Ko’s paintings as part of a continuous process, within an expanded space-time.

《2》 invites viewers to enter a network that traces paintings oscillating between (unperformable) rules and (atypical) configurations. It asks the viewer to join the game, participating in the painting/exhibition as a physical presence, moving beyond the virtual world of screens. As a curator, I want you to re-sense the present and its visual field within the ecosystem of painting. This ecosystem seems to visualize a kind of escape or error while questioning the fragmented space-time and algorithmic behavior recognition of digital media and smartphones.

Games are not an unfamiliar language in art. From recent works that follow the grammar of video, web, and digital games to earlier examples like Fluxus, games have long been integrated into artistic practices; As simulations, possibilities for anomalous thinking, games reconsider the old fashioned art. George Maciunas follows Duchamp’s insistence that “every chess player is an artist”[4] and calls for a “purge of bourgeois banality, of intellectuals, experts and commercialized culture, (…) exterminate imitation, artificial art, abstraction, and reproduction.”[5] Another Fluxus member, Ken Friedman, spoke of the game of art as a “paradigm-shifting play.” Their games, with their emphasis on radicality and playfulness, could be seen as working against the (painting) medium rather than for it.

Ko’s games, however, function for painting and attempt to establish a structure that culminates in painting. The exhibition asks whether Ko’s “method” considers the medium of painting itself and the conventions that condition it as a kind of ready-made or found object. Furthermore, by setting up painting as an already mixed medium (intermedia), an incomplete image, it hypothesizes a situation where the game is set in motion, expanding into a game/network of another reality.

Here, one might ask why “abstract painting” is being re-read as concrete specificity, and why the notion of universality it implies is being replaced by the anti(/non) aesthetic logic of games. The exhibition still sets the “incompleteness” of the universal as the object of reading and translation. By approaching the universal from the point of the specific, and reconsidering the metaphorical nature of the medium, it imagines a scene where abstract painting/exhibition occupies a slightly different function and temporality today.

《2》 places Ko’s paintings in a continuous time and space of past-present-future or here-and-there. Although likened to a game, the exhibition does not follow the usual definition[6]: it has no obstacles or goals, no procedures or competitions, and no winners and losers. When contemporary art itself is likened to a gloomy “end game,” what kind of game could this exhibition play? Could it open up another event as a variation and extension of the method and process, not as an end game predicated on failure, but as an attempt to leapfrog the present of familiar generality, of incomplete universality, and even to say that it has been entirely within (painting/exhibition/art medium)? Let the game begin. The words you will need are:

Fill in the blanks, Triangles, Trajectories, Repaint, and Scatter papers.

That’s all you need to know.

Hyukgue Kwon

[1] Interim, which opened in September 2023, is an “artist-run space created in part of the three artists’ collaborative studio” that hosted “three solo exhibitions (including Geunho Ko’s solo show), two two-person exhibitions, and a group exhibition and a performance programme,” and announced its closure on 10 July.

[2] For an explanation of “some of the methods/rules” mentioned in that paragraph, from Artist’s Notes (2024).

[3] For example, in his 1961 article “How to read a painting – Adventures of the mind”, art historian Ernst Gombrich analyses the details of Maurits Cornelis Escher’s labyrinthine paintings, explaining that there is more to art/images than meets the eye.

[4] See, Bernard Marcadé, Marcel Duchamp: La vie à credit (FLAMMARION, 2007).

[5] Cited from George Maciunas, Manifesto (1963, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection).

[6] See, Jesper Juul, Handmade Pixels: Independent Video Games and the Quest for Authenticity (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2019)