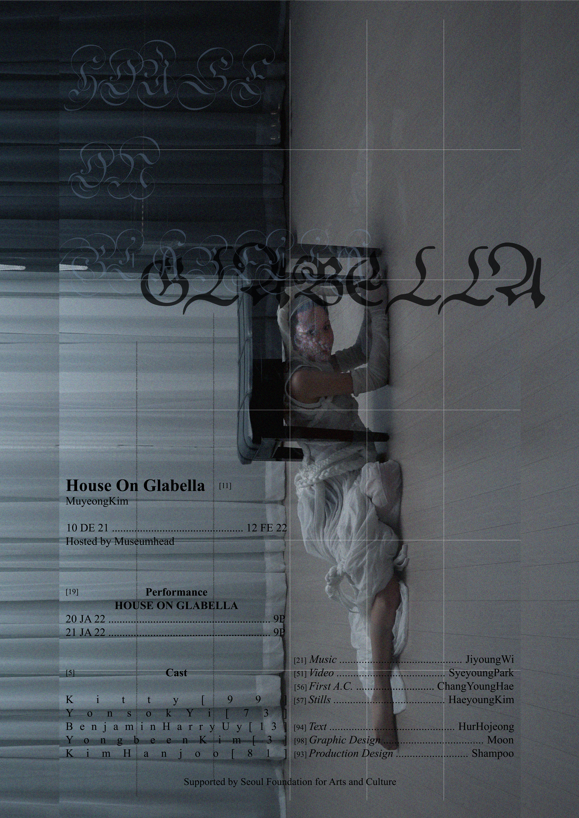

《House On Glabella 미간 위 집》

김무영 개인전

2021.12.10. – 2022.02.12.

기획/글: 허호정

그래픽 디자인: Moon

프로덕션 디자인, 설치: Shampoo

협업 작가: 이연석

사진 설치 협력: 민혜인

웹퍼블리싱: 기예림

도움: 이창현, 장영해, 위지영

주최: 뮤지엄헤드

후원: 서울문화재단

《House On Glabella》

Muyeong Kim

10.DEC.2021.- 12.FEB.2022.

Text: Hojeong Hur

Graphic Design: Moon

Production Design: Shampoo

Collaboration: Yonsok Yi

Photography Installation Cooperator: Hyein Min

Web Publishing: Yelim Ki

Thanks to: Chang Hyun Lee, Young Hae Chang, Jiyoung Wi

Hosted by: Museumhead

Supported by: Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture

[퍼포먼스]

House On Glabella 미간 위 집

뮤지엄헤드

1월 20일 오후 8시

1월 21일 오후 8시

캐스트: Kitty, 이연석, Benjamin Harry Uy, 김용빈, 김한주

음악: 위지영

Hog: 작곡 위지영, 작사 김무영, 연주·노래 김한주

영상: 박세영

영상 보조: 장영해

사진: 김해영

글: 김무영

진행: 허호정

진행 보조: 윤혜아

[Performance]

House On Glabella

Museumhead

20 JA 8P

21 JA 8P

Cast: Kitty, Yonsok Yi, Benjamin Harry Uy, Yongbeen Kim, Kim Hanjoo

Music: Jiyoung Wi

Hog: Jiyoung Wi, Muyeong Kim, Kim Hanjoo

Video: Syeyoung Park

First A.C.: Chang Young Hae

Stills: Haeyoung Kim

Text: Muyeong Kim

Managed by: Hur Hojeong

Staff: Yoon Hye A

미간은 두 눈 사이의 중심에서 시선의 역동을 요약한다. 누군가의 응시에 적나라하게 노출되었다는 느낌이 미간 혹은 코 끝으로 좁혀 드는 때가 있다. 벗어날 길 없는 응시의 자장에 포획된 피식자는 마치 총구가 겨누고 있는 듯 뜨거워지는 눈썹 사이를 의식한다. 반대로 미간은 시선이 후퇴하거나 수거되는 자리가 되기도 한다. 내가 어딜 보는지 상대가 알아채지 못하게 할 때에도 눈썹 사이가 반응하는 것이다. (내가 나 자신의 미간을 본다고 말할 수 있을까?)

미간 위 집은 복수의 시선이 교차하는 세계를 빗댄다. 세계는 적어도 둘 이상의 렌즈에 둘러싸인다. 양쪽 눈, 눈 위로 포갠 안경 알, 손에 들린 스마트폰, 사방의 폐쇄회로, 블랙박스, 그리고 타인의 수많은 눈 들이 부딪치고 어긋난다. 이쪽에서 본/보이는 장면이 저쪽에서는 보이지 않을 수 있고, 내가 던진 시선이 항상 타자의 시선에 맞닿지는 않는다. 둘 이상의 렌즈로 시각화 되는 세계에는 가시성의 불균형이 끊임없이 차이를 만든다. 렌즈들은 서로 다른 시간의 폭을 점유하고 있다.

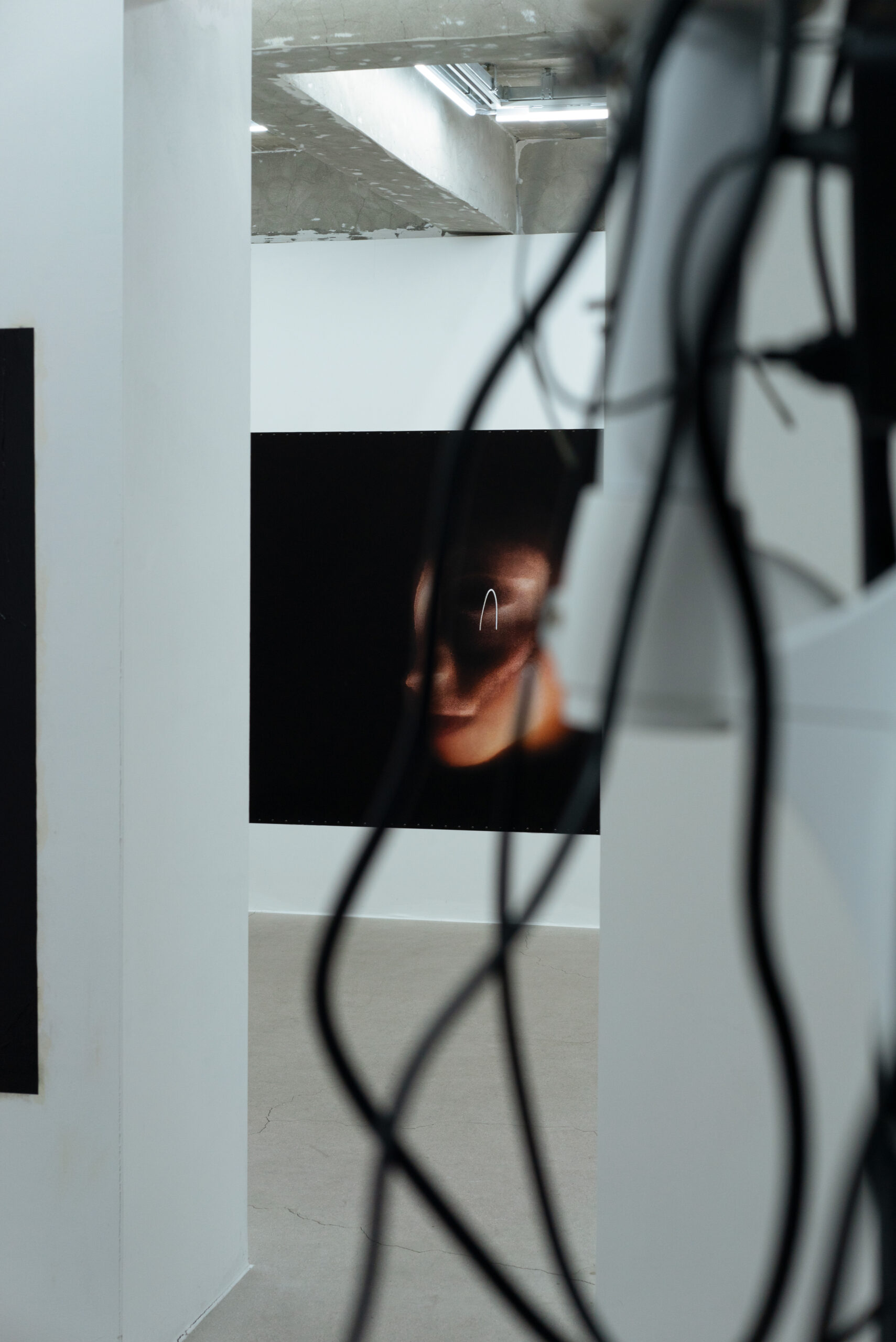

첫 번째 개인전 《House On Glabella 미간 위 집》에서 김무영은 전시장을 눈(들) 사이의 공간으로 여긴다. 그리고 ‘하나’가 될 수 없는, 겹치는 동시에 갈라서는, ‘적어도 둘 이상의 렌즈’로 분열하는 시각의 운명을 주제 삼는다. 그가 주력하는 매체인 퍼포먼스는 렌즈의 다양화와 양적 증가에 대응하는 시각 예술이다. 이때, 공연과 영상 안팎에서 이루어지는 온갖 시선의 교환이 관건이다. 전시라는 특정한 타임라인 위에는 교차하는 가시성의 영역들이 재편된다.

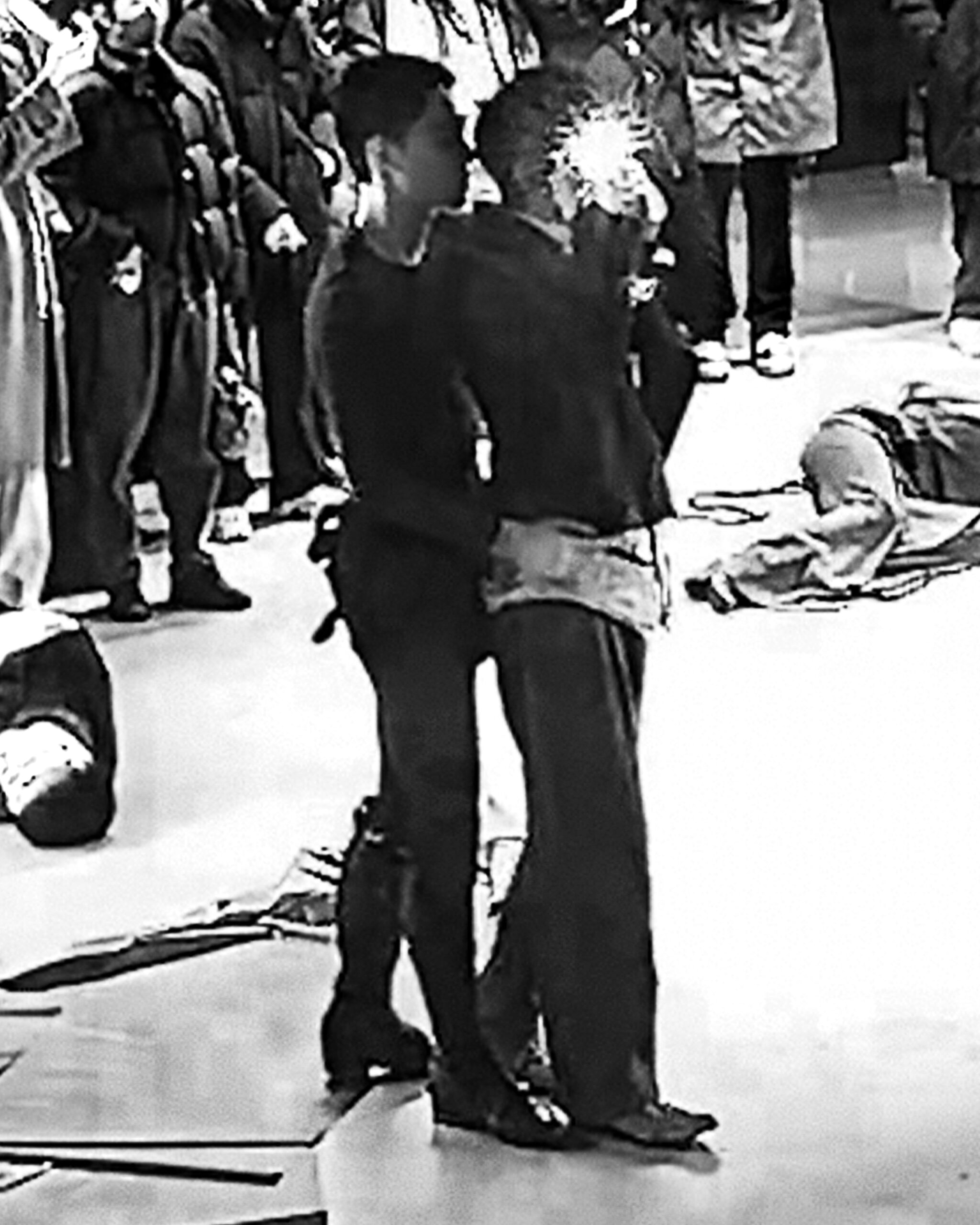

<Socket: Lateral Exits, Chiaroscuro as a Predicament, Dollhouse>(2021)(이하 <Socket>)는 작가가 샴 쌍둥이 분리 수술 다큐멘터리를 본 데서 시작되었다. 이 작품에서 샴 쌍둥이라는 대상화된 인체는 양편으로 갈라지는 시각 경험의 분열적 모델로 상정된다. ‘샴 쌍둥이’ 역할에 캐스팅된 ‘모녀’는 외양적으로 닮았을 뿐 아니라 그 닮음을 웃도는 물리적 동일성으로 무장하고 영상에 긴장을 더한다. 모녀라는 인격적 관계가 하나의 몸에서 갈라진 두 시선을 실현하기 때문이다. 이를 강조하듯 영상은 두 인물이 유사한 동작을 수행하는 장면을 따로 촬영하면서도 한 데 겹쳐 놓는다. 또, <Socket>에서는 핸드-헬드 촬영 방식이나, 패닝, 돌리 샷에 의존하는 롱테이크가 두드러지는데, 이는 앞서 언급한 다큐멘터리에서 쌍둥이의 분리 수술이 담기는 전후 지점에 사용된 촬영/편집술을 가져와 자체의 운동법으로 삼은 결과다. 여기에 저화질 해상도와 그에 따른 노이즈가 더해지면서 영상 화면은 선명함보다 강렬한 직접성을 재현한다. 한편, 러닝타임 말미에 등장한 까만 화면과 그것이 서서히 흐려지며 나타난 줌인 된 두 눈은, 퍼포머나 퍼포먼스 자체에 귀속되지 않은 제3의 시선을 시사하기도 한다.

<Bed Confession>(2021)에서는 프레넬 렌즈의 사용이 두드러진다. 프레넬 렌즈는 표면에 수많은 동심원의 홈을 파서 평평한 유리면이 볼록 렌즈의 효과를 내도록 한 것으로, 원근의 법칙에서 한참 벗어난 상을 보여준다. 영상에서 렌즈는 인물들의 신체 부분이나 얼굴을 지나치게 크게 보이게 하거나 왜곡하기 위해 사용된다. 퍼포먼스 안에서 인물들은 관객의 눈을 의식하고 응수한다. 관객의 시선이 놓일 만한 매 지점에 상반신 크기의 프레넬 렌즈를 앞세우고, 그 뒤로 몸(들)을 감추어 신체를 향하는 시선(들)을 튕겨내는 것이다. 적중하지도 교환되지도 않는 시선의 실패는 한 침대에 앉은 두 퍼포머 사이에서도 마찬가지다. 작품 안팎에서 시선은 실패하고, 등장 인물의 야릇한 몸짓을 뒤쫓는 관음적 욕망 역시 좌절한다.

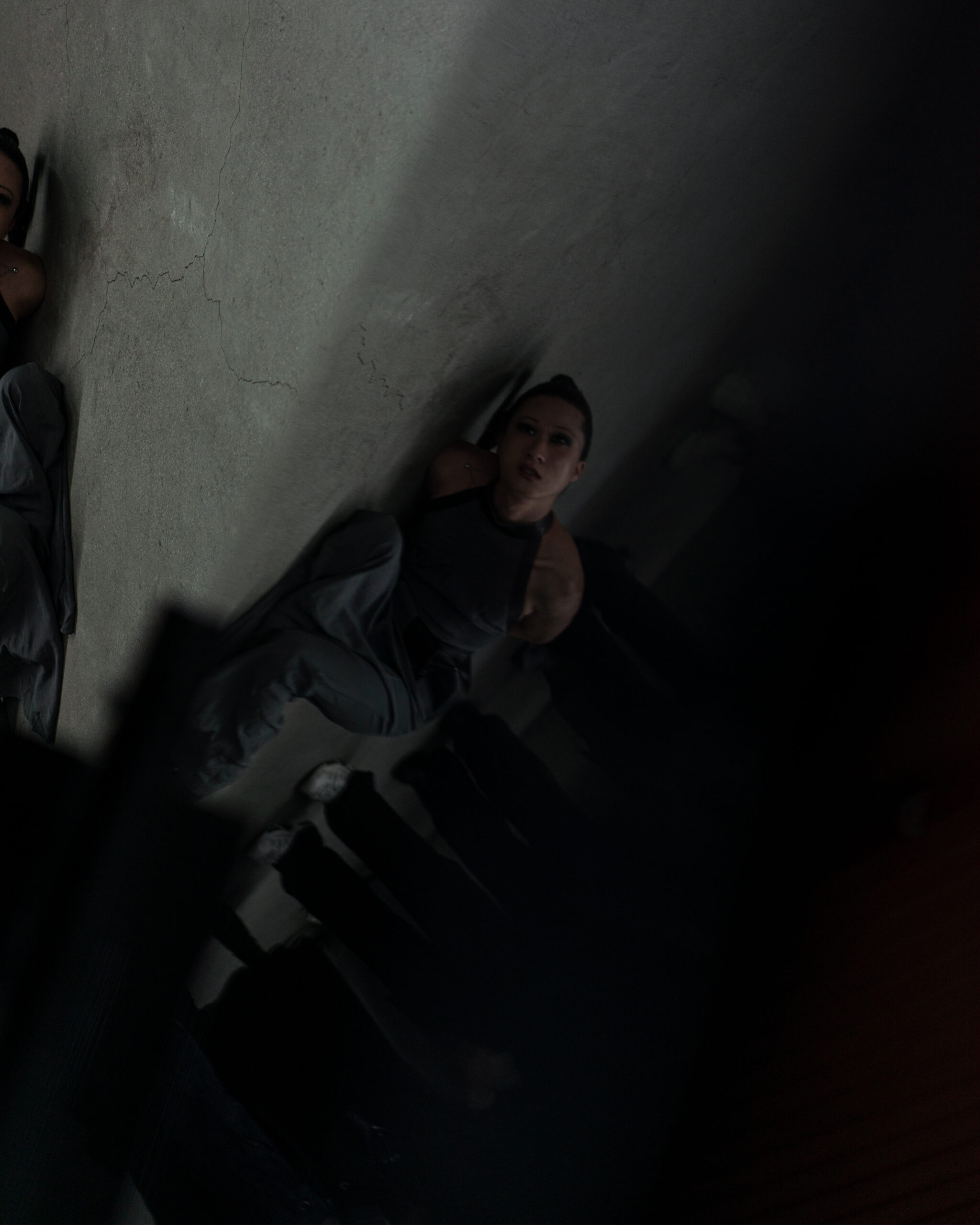

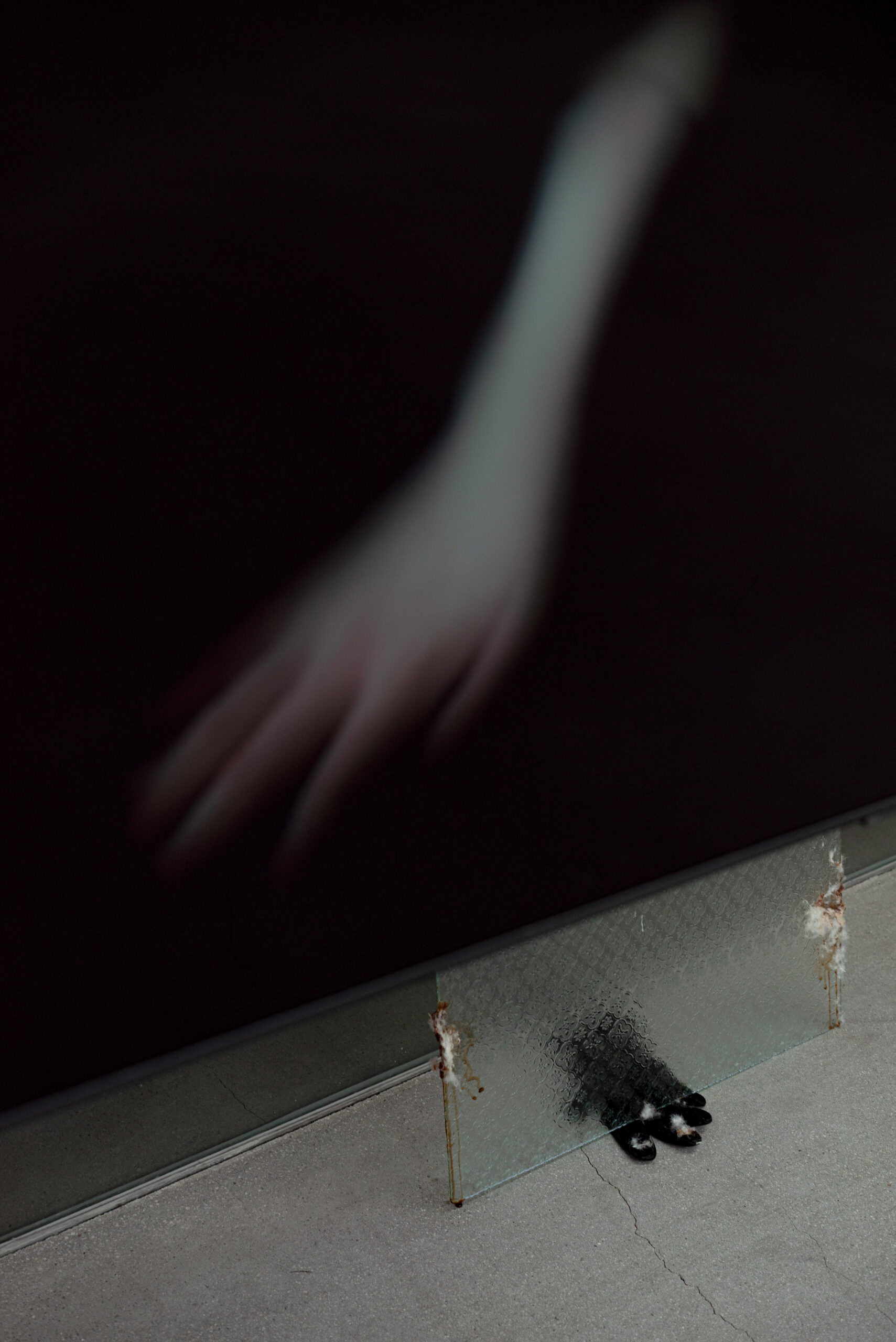

<Why you two never look at me>(2021)는 아이폰 카메라의 무대조명 모드로 촬영된 인물 사진 연작이다. 아이폰 카메라에 내장된 기본 설정 값인 무대조명 모드는 피사체인 인물을 자동으로 인식하여 얼굴에 해당하는 전경만 환하게 비춘다. 그러면 얼굴 윤곽 밖의 사위 배경은 까맣게 처리되는데, 이 까만 배경 면이 간혹 얼굴을 침범하여 형상을 일그러뜨리는 경우가 있다. 작가는 이러한 전-후경 인식의 오차를 급진적으로 역이용하려 한다. 모드의 자동성을 신뢰하는 채로, 다만 알고리즘이 속도에 반응하는 방식을 교란하는 것이다. 카메라를 거의 집어 던지듯 과격하게 흔들어 사진을 찍는 행위는 의도된 교란과 우연을 동시에 시도한다. 시선의 방향성과 자동성을 지나치게 믿은 나머지 ‘보기’는 불능에 처한다. 그리하여 <Why you two never look at me>는 전통적 의미의 포착을 통해 날 것을 취하면서도, 인물의 왜곡상을 담는다.

김무영의 작업은 천연덕스럽거나 매끄럽게 흘러가는 시선과 속도, 느낌을 자꾸 분절하고 흩트려 놓는다. 따라서 전시에 나타난 다각화 된 렌즈들은 ‘보기’와 ‘형상’의 자연스러움을 배반한다. 하지만 배반의 장면에 비춰진 세계의 면모들이 또다른 매혹을 일으키기도 한다. 이미 도래한 스펙터클의 시대가 섬세하게 관찰, 기록되면서, 가시성에 현혹된 우울, 길티-플레저(guilty pleasure)가 뒤섞인다.

애초에 스펙터클은 프로시니엄 무대 위에 오른 마술과 같았다. 마술의 미덕은 그럴듯한 이유나 과정을 보여주지 않고도 결정적 장면에 도달하는 비약 자체에 있었다. 조금만 각도를 달리해도 결정적 장면의 이면이 노출되기 때문에 (그러면 이미지의 효과가 반감하기 때문에) 마술사는 운신의 폭을 좁히고, 의심의 눈초리를 피해야 했다. 그런데, 사람들이 더 이상 정면을 응시하거나 관조하는 마술쇼에 만족하지 않게 되었다면 어떨까? 오히려 사람들은 마술을 가능하게 하는 미시적인 장치들과 구조를 미리 파악하는 데에 열을 올린다. 우주적 규모를 자랑하는 SF 영화는 개봉 전에 어떤 CG 기술을 이용하고 실사는 어느 정도 비율로 사용했는지, 크로마키 배경 위에서 배우의 연기력은 어떻게 구성되었는지 보여주어야 한다. 스타가 오랜만에 복귀하는 액션 영화는 그가 스턴트맨에게 얼마나 의존했는지, 혹은 그러지 않았는지 증언해야 한다. Youtube에는 각종 메이킹 필름뿐 아니라, 명장면을 DIY로 재현할 수 있는 튜토리얼이 시시때때로 업데이트 된다. 이 모든 상황이 스펙터클의 효과와 기대를 누그러뜨리는 것은 아니다. 마술의 폭로된 이면은 속임수의 과정마저 스펙터클화 한다. 스펙터클도 분화하는 것이다.

눈 앞에 펼쳐지는 생생한 사건(live event)으로서의 퍼포먼스와 그것의 기록에 관한 이야기들은 이 같은 맥락에서 크게 벗어나지 않는다. 퍼포먼스에서 생생함이 보증하는 스펙터클적 면모는, 그 현시성이 상실되는 때에 실패하는 것으로 여겨졌다. 마술사의 기교가 현장의 정면에서만 관람 가능한 한에서 마술이 성공하는 것처럼. 그러나 스펙터클을 스펙터클이 되도록 만드는 일련의 (비)가시적 절차가 역으로 조명받게 되었듯이, 퍼포먼스는 자신의 비-현시적, 자기반복적, 복제가능한 요소들을 포섭하게 되었다.

<Fault (in three folds)>(2019)와 <Sun gun>, <Murmur>, <Old Vessel>(2021)은 <Nimbus>(2019)의 부분이자 전체다. 이들 작품은 전시장에서 볼 수 없는 어떤 퍼포먼스를 가리키고, 그럼으로써 역설적으로 부재하는 무엇을 계속 환기한다. <Sun gun>, <So Annie, are you ok? Are you ok, Annie?>, <Sun gun>, <Murmur>, <Old Vessel>는 <Nimbus>의 레퍼런스로 자처하는 이연석의 회화 작업이다. 이 회화들은 <Nimbus>의 반복인가, 그 자신인가, 그것이고자 하는 열망인가? 혹은 그 무엇도 아닌가. 서로가 서로를 지시하거나 일치시키려는 역학 관계 안에서 두 작가, 그들의 회화/퍼포먼스가 경계를 확인하거나 의심한다. 이로써 부재하는 대상과 현재 눈 앞에 놓인 대상의 합일을 꿈꾸는 시도가 반복적으로 펼쳐지고, 과거-현재-미래의 시간 얼개는 뒤집힌다.

<Fault (in three folds)>는 <Nimbus> 실황 퍼포먼스에 참여한 촬영자를 퍼포머 중 한 사람에 포함시키면서, 그가 다른 퍼포머들과는 차별적으로 부여받게 된 스코어를 문서화한 것이다. 스코어는 1934-68년 미국에서 발효된 ‘프로덕션 코드(The Motion Picture Production Code)’라는 문서를 발췌, 인용하여 재구성한다. 코드는 당시 미국 내에서 생산된 모든 영상물에 있어 외설적이라 간주될 일체의 장면 연출을 규제하는 내용을 담고 있다. 이에 따르면 신체의 노출, 비규범적 성행위/관계, 서사상의 폭력은 제한되어야 마땅하며, ‘잘못된’ 장면은 삭제되거나 시간을 줄여서 방영되어야 했다. 김무영은 <Nimbus>의 촬영자에게 해당 코드가 제안하는 도덕적 규준에 따라 퍼포먼스를 재해석하여 카메라를 움직이게 한다. 그 결과 카메라는 구시대적 ‘도덕률’을 우스꽝스럽게 퍼포밍하고, 으레 기록 영상에게 기대되는 초연한 관찰, 중립적 시선 내지는 ‘있는 그대로’의 기록으로서 역할을 모두 상실한다. 대신 그 자체로 독립해 새로운 시각성으로 기능한다.

전시 기간 중 두 차례 실황으로 진행되는 퍼포먼스 <House On Glabella>(2021)는 스펙터클 드라마의 한 장면을 재연하는 DIY 튜토리얼에서 출발한다. 그러나 이 상연 중인 스펙터클은 드라마에서 빠져나와 마술적 장면의 이면을 보여주고, 바깥의 시선을 개입시킨다. 그 앞에 선 관객은 무엇을 기대하고 봐야하는 지 거듭 회의하게 된다. 스펙터클의 분화된 면면으로서, 흔들리는 시선들을 재배치하는 퍼포먼스는 미간 위에 성을 새로이 쌓는다. 이제 전시장은 특정한 ‘보기’를 강제하던 그 자신의 권위를 상실하고, 일정한 루프에 매여 있던 영상의 러닝타임에서도 탈각해 다른 시간에 접어든다. 퍼포머의 몸, 관객의 몸, 카메라, 안경, 폐쇄회로, 휴대폰을 넘나드는 렌즈들이 각자의 시간을 요청하는 제스처에 반응하면서.

기획/글 허호정

House On Glabella

The small space between our eyebrows, the medical terminology for which is “glabella,” is responsible for the depth and range of emotion that can be conveyed by the human gaze. There are moments when we realize that we are the focus of someone’s probing gaze through their wrinkling of the space between their brows or crinkling of the nose. The prey, having fallen into the inescapable force-field of the predator’s gaze, feels one’s glabella heat up—as if it is being blazed with fire. The glabella is also a spot from which a gaze can be retracted. Even when we have done our best to shield the direction of our gaze from someone else, the one thing we cannot control is the responsiveness of the space between our brows. (Can I, in all honesty, say that I can see my own glabella?)

This exhibition compares this phenomenon to a world of revolving multiple perspectives. It suggests that the world is always encased in at least two lenses. Our eyeballs, glasses lenses, the smartphone (which is always in hand), CCTVs that are now virtually everywhere, in-vehicle data recorders, and the eyes of countless others—all of these collide, refusing or unable to complement one another. Things that are visible from one side may not be from another location, and the direction of my gaze may not coincide with that of someone else. In a world made visible through two or more lenses, imbalance of visible constantly results in differences. Each lens occupies a different block/span of time.

For his first solo exhibition, House On Glabella, Muyeong Kim regards the exhibition venue as one massive glabella, taking as his theme the fate of the gaze: something that can never “become one,” that divides as soon as it overlaps with another, and is always divided into two or more lenses. His medium of choice, the performance, offers art’s response to the diversification and increasing quantity of lenses. The exhibition is defined by the many exchanges of gaze that occur both within and outside of the performances and videos—a reorganization of the realms of visibility that intersect in the clearly-defined timeline that is an art exhibition.

Socket: Lateral Exits, Chiaroscuro as a Predicament, Dollhouse (2021) was inspired by a documentary Kim saw on the surgical separation of a pair of Siamese twins. In Kim’s work, the Siamese twin is an objectified body that serves as the model for a very visceral bisection. The real-life mother and daughter who were cast to play Siamese twins create a tension in the artwork that stems from more than biological similarity. They have a “sameness of substance” that is the result of two perspectives stemming from the same body and that is heightened because of the daughter being the same gender as her mother. The video stresses this fact by filming each woman engaged in similar bodily movements separately and then overlapping the footage. Furthermore, Socket is made up of many long takes, which rely on pans or dolly shots, and hand-held filming—the result of borrowing the filming/editing technologies used by the aforementioned documentary to show what happens just before and after the surgical separation. The incorporation of low resolution mode (and the noise that occurs from this) makes the footage convey a powerful directness rather than clarity. The black screen that appears toward the end and its gradual fading out into a pair of zoomed-in eyes implies the existence of a “third gaze” that is independent of the performance and performers.

Bed Confession (2021) is noteworthy for its prolific use of the Fresnel lens. By making holes in the many concentric circles on the Fresnel lens’ surface to allow flat glass to have the same effect as a convex lens, it shows us images that are far removed from the rules of perspective. In the video, the lens is used to make the actors’ body parts or faces look excessively large or distorted. The characters are conscious of the audience’s gaze and tailor their responses to it. Each point that is expected to catch the viewer’s attention is installed with a Fresnel lens that is approximately the size of an adult torso: the lens hides the body (or bodies) behind it, effectively reflecting the gazes that are focused on the body. The failure of gazes to dovetail or even exchanged also applies to the two actors on the bed: gazes, both inside and outside the artwork, fail to find a place to rest. The voyeuristic gaze, which desires the erotic physical movements of the video’s characters, also fails.

Why you two never look at me (2021) is a series of portrait photos taken with an iPhone camera’s Stage Mode effect—a basic function that automatically perceives the subject’s face and blackens the background to illuminate only the face. This black background, however, sometimes moves into the face, thereby temporarily distorting it. What Kim turns against itself, very radically, is such discrepancies in the perception of foreground/background. This is done based on the automated functioning of Stage Mode, by simply disrupting the way it responds to the algorithm’s speed. Photos that are taken with a camera that is essentially being thrown around are, inevitably, blurry: they are the outcome of both coincidence and (intentional) disturbance. Excessive faith in the gaze’s directionality and automated nature results in photos that are all but impossible to view normally. Through its grasp of the traditional notion of “meaning,” Why you two never look at me portrays subjects in their raw state while distorting the human form.

Kim’s work scatters and cuts up unaffected, smoothly-flowing gazes, velocities, and moods. Because of this, the diversified lenses that appear in this exhibition betray the naturalness of the act of seeing and the concept of shape. The aspects of the world that are displayed through such scenes of betrayal, however, are also quite attractive. The detailed observations and records made by the already-arrived “age of the spectacle” are mixed up with depression and guilty pleasure, which have been deceived/misled by visibility.

The spectacle, originally, was a magic show performed on a stage’s proscenium. The virtue of the magic show is the glossing over of process and causality to show the audience only the most defining moments. Because even the slightest tilting of angle can expose aspects of important scenes that audiences are best left in the dark about (due to the potential decreased impact of such scenes), the magician had to be very careful about each of his movements to avoid the audience’s suspicious gaze. What, then, happens once people are no longer satisfied with the magic show, which requires them to look only straight ahead? They start trying to obtain information about the devices and structures that make such magic shows possible. The science fiction film, which, by nature, involves a gargantuan production and usually, before its release, show which CG technologies were used, the size ratio of the actual props/set compared to how they appear in the film, and how the actors acted their scenes in front of a green screen. An action actor who is returning after a long filming hiatus must be able to say how much they relied (or did not rely) on their stunt double. YouTube is now constantly updated with various “making film” clips as well as tutorials on how to reenact famous scenes. It must be noted that none of these activities diminishes the effect of and our expectations of the spectacle itself. The act of revealing the magician’s trade secrets has itself become a spectacle—a splitting of the spectacle into two shoots.

The division of the performance as an ongoing live event and the record of how it is created is similar to the way that spectacles are consumed today. Thus far, a performance’s spectacular quality that had lost its here-and-now-ness was regarded as a failure—just as the magician’s skills can only be viewed on-site without turning one’s head to the side in order for the magic show to succeed. However, just as the visible/invisible processes required to make a spectacle are now the subject of attention themselves, our attention is directed to the non-here-and-now, self-repetitive, and replicable aspects of the performance.

Fault (in three folds) (2019), and Sun gun, Murmur, and Old Vessel (2021) are all part of—and the entirety of—Nimbus (2019). By serving as witnesses throughout the exhibition venue about a performance that we cannot see, they, paradoxically, make us constantly aware of what is absent. Sun gun, So Annie, are you ok? Are you ok, Annie?, Murmur, and Old Vessel are paintings by Yonsok Yi that explicitly reference Nimbus. Are these paintings a repetition of, an embodiment of the essence of, or the desire to be such representation of Nimbus? Or are they none of these things? Within their relationship dynamic (of supporting or coinciding with one another), the two artists are constantly verifying or being suspicious of the boundaries of the paintings/performances. It is in this way that attempts are repetitively made to unite the absent entity with what is before us, thereby constantly disrupting the temporal structure of past-present-future.

Fault (in three folds) includes one of the film crew for Nimbus as a performer: it is the documentation of the directions that this new performer was given (and this was different from what the others were given). These directions were an adaptation based on sections of The Motion Picture Production Code, which was promulgated in the US between 1934 and 1968 and regulated the staging of scenes in all domestic films that could potentially be regarded as not “wholesome” or “moral.” According to this document, “nudity, anti-normative sexual relationships or acts, and graphic or realistic violence were prohibited,” with scenes including any of these things required to be deleted or drastically reduced. In Nimbus, the cameraman films the performance while adhering to the ethical standards outlined in the above-mentioned code. Such “loyalty” to an outdated ethical code results in some truly ludicrous camerawork, which in turn results in the resulting film being completely devoid of an aloof observatory stance, neutrality, and “as-is” nature that is expected of a FiLMiC record. It does, however, offer a new perspective as an independent work in and of itself.

House On Glabella (2021), which will be performed twice in real-time while the exhibition is in session, begins from a DIY tutorial on reenacting a spectacular scene from a drama. The spectacle, however, leaves the drama format to show us a lesser-known side of artistic scenes while incorporating an outside perspective. While viewing it, the spectator is constantly disillusioned about what they “should” expect or watch for. The eruption of the spectacle into a performance that actively rearranges those unstable, shaking perspectives reconstructs the house that sits at the top of our glabellas. The exhibition venue is recognized as having lost its authority as an entity that could unilaterally force visitors to engage in the act of viewing. In this respect, for its part, the film has rid itself of its runtime, which was linked inextricably to a certain loop, to enter a new world of time, with the lenses—which now come from the performers’ bodies, visitors’ bodies, camera, glasses, closed circuits, and mobile phones—each responding to the gestures that demand their time.

Hur Hojeong