김민희 개인전

2024.05.03.-06.29.

12:00-19:00 (일요일, 월요일 휴관)

그래픽 디자인ㅣ워크스

설치ㅣ조재홍, 정진욱

주최/주관ㅣ뮤지엄헤드

후원ㅣ서울시, 서울문화재단

Berserker

Minhee Kim solo exhibition

3.MAY-29.JUNE.2024

12:00-19:00 (closed on Sun, Mon)

Museumhead, 1F, 84-3, Gyedong-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul

Graphic DesignㅣWORKS

Artwork InstallationㅣJaehong Jo, Jinwook Jung

Hosted and Organized by Museumhead

Supported by Seoul, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture

당신은 수세기 전부터 의혹의 대상이 되어왔던 형체를 바라보고 있다. 당신은 그만둔다.

– 마르그리트 뒤라스[1]

전시 제목인 ‘버서커(Berserker)’는 중세 신화에 등장하는 전투광을 가리킨다. 버서커는 주로 늑대가죽을 뒤집어쓰거나 벌거벗은 채 광기에 휩싸여 전쟁에 임했다고 전한다. 오늘날 버서커는 게임 캐릭터로 자주 재현되며, 그 이름을 부르는 방식이나 형상화 방식은 각 언어권/문화권의 하위문화에서 다양하게 나타난다. 이번 전시에서 김민희는 버서커를 어딘지 익숙한 여성 캐릭터의 모습으로 묘사한다.

그림들이 제시하는 인물형상(figure)은 기시감을 전한다. 가까이는 게임 콘텐츠, 애니메이션으로부터 멀리는 중세 성화까지, 여성 캐릭터의 재현 양상이 상당히 제한적으로 유사한 데에서 이 기시감의 이유를 찾아볼 수 있다. 반복된 재현의 조건들 — 보기 좋다 여겨지는 인체 비율, 부각된 가슴, 가슴-허리-엉덩이로 이어지는 선적인 묘사, 그 모양을 강조하는 의상.

작가는 아마도 자기 자신일 초상을 스스로 욕망한 대로 그리기를 욕망하면서, 끝내 상투적인 이미지들에 의존했을 것이다. 부지불식간에 말해지고 마는 기표가 자신이 아닌 타자의 욕망을 반영하기 마련인 것처럼 말이다. 하지만, 거꾸로 말해, 이 단독 초상들은 익숙한 재현의 도상을 따르는 한편 그것을 다시 체화하는 김민희 식의 한 경로를 보여준다. 어떻게 같으면서 또 다를 것인가? 유사(동일시)는 차이를 낳고 어디에 도달하는가?

우선, 김민희는 이미지가 아닌 회화로 관객의 주목을 유도한다. 여기서 ‘이미지’라는 말은 으레 그렇듯 약간의 경멸조를 포함해 사용된 것이다. 바야흐로 이미지 시대인 오늘날, 이미지란 매체(medium)와 몸(body)을 떠난 휘발성의 무엇으로, 무한히 생산 ∙ 재생산 ∙ 편집 ∙ 소비되는 자본주의 오브제 일반의 양상을 가리키기 위해 쓰인다. 이때, 미술가가 고민하는 이미지는 보다 구체적이고 실질적인 하나의 형식으로서, 매체-몸과의 불가분 상태를 드물게 발생시키는 것이 되어야 한다. 그리하여 전시 《버서커》는 현전(presence)으로서의 이미지, 회화-몸으로서의 이미지를 드러내 보이려 한다.

어쩌면, 이제껏 김민희는 ‘경멸스럽지만 결코 떨쳐낼 수 없음’을 특징으로 하는 가벼운 이미지들을 다뤄왔는지도 모른다. 일테면, 디지털 기술 매체의 미감이라 할 수 있을 글리치(glitch)의 문제가 있다. 김민희 작업에서 명료한 윤곽 대신 도입된, 의도적으로 형상을 뭉개는 이미지 표현은 글리치적인 것, 글리치를 코드화하는 것으로 이해되었다.[2] 이는 언제든 자기-모방될 수 있고 자기-복제될 수 있는 동시대 이미지의 성질을 역설적으로 긍정하는 하나의 방편이었다. (2021년 개인전 《이미지 앨범》(실린더, 서울)이 어떻게 가상으로부터 (존재하지도 않았던) 원본을 유추하게 했는지를 떠올려보자.) 그러나 따지고 보면, 김민희 그림에서 글리치적인 것은 실제 글리치와 같이 우연히 발생한 것이 아니고, 마치 글리치‘처럼’ 보이도록 심어진 이미지 조각에 다름 아니었다. 표면 위를 배회하는 알 수 없는 입자들은 최종적인 형상 안으로 수렴, 결과적인 이미지를 완성시켰다. 이처럼 디지털 기술의 한 효과로서 글리치는 그 자체 이미지로 추출되어 또 다른 이미지의 일부가 된다.

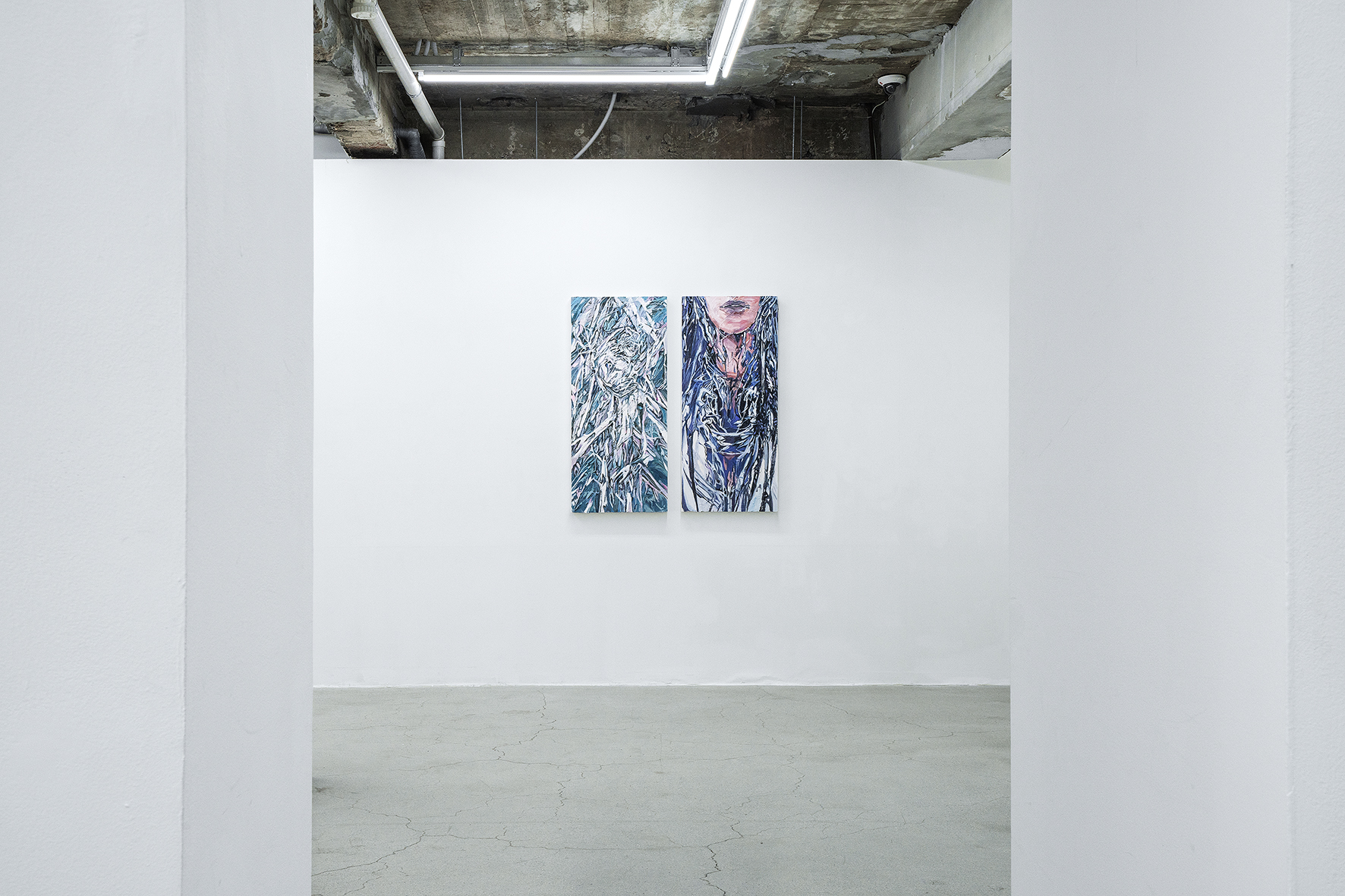

이와는 반대로, 이번 전시에서 그림은 떼어 붙여 증식하는 ‘이미지’ 생성 원리를 따르지 않는다. 차라리 주어진 공간의 안팎으로 존재를 발산 ∙ 감지하게 하는 덩어리를 강조한다. 중요한 것은 끊임없이 이미지가 생성되는 기계적 논리가 아니라, 물질이 그것을 지지하고 보존한다는 사실이다. 작가는 캔버스 위에 층을 쌓아 올리고 붓질을 따라가며, 고전적 의미에서의 흔적들로 화면을 채운다. 지지체 위를 비선형적으로 가로지르며 겔 미디움을 이용한 난삽한 드리핑이 흥미로운 기층을 만들고, 이와는 무관하게 그러나 때로는 조응하는 붓질이 더해진다. 지지체의 가장 바깥 층까지 거듭 지속된 붓질은 안료의 치덕치덕한 덧댐을 장식하듯 펼쳐 보인다. 평면을 따라 번지기만 하지는 않고 오히려 지지체에 심도를 마련하는 이 흔적들은, 이곳의 현전과 분리되어 어떤 ‘이미지’가 떠돌아다니도록 내버려 두지 않는다. 그것은 형상을 보충하기도 하지만 자주 방해하며, 언제나 그림 자체의 물리적 두께를 확인시킨다.

말하자면, 이 물리적 두께는 그림에게 옷이 된다. 그림이라는 몸을 감싼 베일, 그 베일 자체가 문제시되는 그림이 김민희 회화라고 할 수도 있겠다. 특히, 이번 전시에서는 캔버스가 웬만한 사람의 키에 근접하거나 훌쩍 넘도록 거대하기에 관객은 그림을 전체적으로 조망하기보다 장소 안에서, 부분만을, 가까이 들여다보게 된다. 이때, 이미지와 거리를 좁혀 나가는 접촉의 감각이 활성화되고, 보는 사람은 가장 먼저 바깥의 베일들을 감지한다. 이것은 형상 차원에서나 실질적인 사물(캔버스 오브제) 차원에서나 마찬가지다. 옷 ∙ 피부 ∙ 날개 ∙ 덩굴 ∙ 밧줄 등으로 (더욱이 의미를 알 수 없는 단지 얼룩으로) 드리운 베일은 형상으로서의 몸, 어떤 여자 이미지를 덮고 가릴 뿐 아니라, 폭과 높이, 두께를 가진 캔버스 자체를 덮고 있다.

이렇듯 일종의 베일로 기능하는 회화의 물질적 층위는 좀 더 해명을 필요로 한다. 계속해서 무언가 성가시게 눈/촉각을 괴롭히는 이 옷자락은, 그것을 거두어(벗겨내어) 안을 들여다보고 싶게 만든다. 그림은 벗겨냄을 자극하고, 결국 몸이 알맹이를 드러난다. 물론 이 몸은 피복과의 복합적인 관계 속에서만 모습을 드러낼 것이다. 각 그림에서 몸은 꾸준히 베일만큼이나 문제적으로 조명되는데, 이 역시도 형상과 물리적 차원 모두에서 그러하다. 형상 차원에서 팔과 다리, 허리 등 곡선이 강조되는 몸의 부분은 지나치게 길게 늘어나 있고, 정확히 무엇이라 가늠하기 어려운 선의 표현이 몸을 찌르듯 파고들거나 심지어 관통한다. 몸은 훼손되고 왜곡되고 변형을 포함한다. 물리적 차원에서 베일은 그림을 구성하는 지층들을 강조하며, 어떻든 형상을 찾으려는 본능적인 욕구를 덩어리 진 전체 속에서 헤매게 만들고, 결국 그 질감, 색, 빛과 부피감만을 남긴다.

한편, 그림에서 옷과 몸(피부, 근육)이 정확히 구분되지 않고 있다는 점을 눈 여겨 보자. 단적인 예로, 〈변태metamorphosis〉(2024)에서 옷은 푸른색의 비키니 형으로 표현되었는데, 그 외에도 팔, 다리, 흉부에 해당하는 위치에 푸른색 자국들이 모호한 인상을 남긴다. 저 푸른색 자국은 옷으로도 보이지만, 갈비뼈를 드러내 몸의 안팎을 뒤집어 보여주는 듯도 하고, 피부 자체나 좀 더 깊은 근섬유의 조직을 노출하는 듯도 한 것이다. 일종의 섬유 가닥이 덩어리를 찢고 통과하는 듯한 모양으로 몸 밖으로 방사될 때, 몸은 정지된 자세(posture)를 극복하고 꿈틀대며 움직인다. 그의 얼굴은 잘린 채라 시선의 교환은 원천 차단되고, 무엇보다 옷과 몸의 관계—무엇이 무엇을 가리고 벗겨 보이는지—가 모호한 상태에서 관객은 가만히 저 몸을 감상할 수가 없다. 어딘지 고통에 몸부림치는 것 같은 몸은 이제 막 다른 것으로 변신해 버릴 참이다.

변신? 무엇으로? 알 수 없지만, 변신의 예감은 주어진 이미지를 하나의 잠재태, 운동 중인 상태로 바라보게 한다. 이렇게 말해볼 수도 있다. 우리는 그림들 앞에서 다만 ‘벌거벗음’을 기다리고 있는 중이라고. 조르조 아감벤(Giorgio Agamben)은 ‘벌거벗음’이 상태가 아니라 오로지 사건으로서만 확인 가능하다고 말했는데, 그 이유는 몸이 (의복 또는 은총의) 덧입음을 벗어나는 순간에만 벌거벗음이 벌거벗음으로 인식되기 때문이다. 그림에서 인물은 ‘누드’ 상태가 아니고, 따라서 하나의 상태로 인식되는 ‘벗음’은 없다. 다만, 엉겨 붙은 피부-몸-옷이 서로를 가리는 베일로 위치하며, 베일이 벗겨지는 사건, 몸의 변신, 발가벗겨짐 자체를 예비하고 있다.

벌거벗음, 그것은 외설인가? 우리는 다시, 이 그림들에서 대중적으로 소비되는 여성 캐릭터의 원형을 마주한다. 자주 외설적으로 묘사되며 남성적 시선 아래 관음과 페티시 대상으로서 유효했던 신체들을 발견할 지도 모른다. 김민희는 그러한 상투적 재현들에 대해 한편으로는 어쩔 수 없다는 듯 자기를 투사하고, 다른 한편으로는 그것을 재조정함으로써 새로운 쾌락의 차원을 발견하려 한다. 몸을 옭아 매던 타자의 시선은 오히려 벌거벗음—근육과 내장을 뒤집어 보이고 세계와 몸의 경계를 흐리도록 확장하는 벌거벗음—을 가능케 하는 모종의 동력을 제공할지도 모른다.

우리는 《버서커》에서 벗겨짐을 경유해 몸을 본다. 물질의 베일이 물질의 틈을 벌려 이미지를 벌거벗기는 회화에서, 너무도 익숙한 모양으로 나타난 여체(女體)는 베일들의 놀이 속에 몸의 운동을 확장한다. 그림으로 물화된 몸은 욕망과 이미지 양자를 초극하는 변증법을 이뤄낼 수 있을까. 몸은, 이미지-덩어리로서 그림은, 다만 여기 전시된다.

글 허호정

[1] 마르그리트 뒤라스(조재룡 옮김), 『죽음의 병』(파주: 난다, 2016), 43.

[2] 디지털 컨텐츠를 일상적으로 접하다 보면, 순간적으로 화면이 깨지거나 멈추는 등의 일시적인 오류를 겪어본 적이 있을 것이다. 시청각적으로 인지되는 오류의 흔적들(버그 또는 글리치)이 많은 예술가들에게 하나의 계기를 마련했다. 가령, 글리치는 미끈한 회로에서 벗어날 하나의 반(反)체제적 틈으로 전망되거나, 그 우발성과 물질적 기반 없음 때문에 더 많은 자유를 의미하는 듯 여겨졌다. 그런데 시간이 다소간 흘러 글리치는 하나의 미감이 되어, 문화 전반에서 활용된다. 이제 글리치는 회로의 틈이 아니라 액세서리로, 다시금 거대한 흐름 속에 편입된다.

You look at the shape suspected through the ages. You give up.

– Marguerite Duras[i]

The title of the exhibition, Berserker, refers to the battle fanatic from medieval mythology, known for engaging in combat in a frenzied state, often dressed in wolf skin or completely naked. Today, berserkers are commonly depicted as characters in PC and web games, with variations in their names and appearances across different subcultures. In this exhibition, KIM Minhee reimagines the berserker as a familiar female character.

The figures depicted in the paintings evoke a sense of familiarity, almost like déjà vu. From recent media such as games and anime to classical religious art, we are accustomed to certain conventions in the depiction of female characters. Similarly, the portrayals in this exhibition display familiar attributes of female representation: idealized proportions, prominent breasts, and clothing that accentuates the “shape.”

The artist, perhaps in an attempt to depict herself as she wishes to be perceived, ultimately resorts to clichés—the conventional representations. It’s as if, “le désir de l’homme, c’est le désir de l’Autre” (the desire of man is the desire of the Other). Yet, these solo portraits reveal one trajectory in KIM’s practice, one that adheres to representational conventions while simultaneously reinterpreting them. How does one maintain sameness while also embodying difference? Where does resemblance (or identification) diverge into distinction?

First and foremost, the artist directs the viewer’s attention to the paintings rather than mere images. The term “image” carries a slightly negative connotation here, as it is often said that we are currently in “the age of images,” where images are ephemeral entities detached from both medium and body. However, in KIM’s work, the image she concerns herself with takes on a more tangible form, one inseparable from both medium and body. The exhibition Berserker aims to reveal the image as a presence and the image as a body of painting.

Until now, the artist has grappled with “images” marked by a “disdain yet inability to shake off.” One prominent example is the concept of the “glitch,” often associated with the aesthetics of digital technology. In KIM’s paintings, intentional distortions and disruptions in shapes, which replace clear outlines, have been interpreted as glitches, thereby codifying glitchiness.[ii] This approach paradoxically affirms the self-mimetic and self-replicating nature of contemporary images, which can be reproduced endlessly (as seen in her 2021 solo exhibition, Image Album, at Cylinder, Seoul, which inferred a non-existent original from a virtual one). However, what appears glitchy in KIM’s work is not the result of accidental occurrences (as “real” glitches are) but rather fragments of images deliberately arranged to mimic glitches. These unknown particles hovering over the surface converge to form a final shape, ultimately completing the resulting image. As an effect of digital technology, the glitch is extracted into its own image and then becomes part of another.

In contrast, the paintings in this exhibition don’t adhere to the principle of creating “images” through copying and pasting (or extracting and repeating). Instead, they emphasize masses that radiate presence within a given space. Here, the focus isn’t on the mechanical logic of (auto)generation but on the material that supports and preserves these images. The artist layers the canvas, filling it with ‘traces’ in a classical sense. Chaotic drips of gel medium spread across the support in a non-linear fashion, creating an intriguing substratum onto which unrelated yet occasionally coordinated brushstrokes are added. These repeated brushstrokes extend to the outermost layers of the support, unfolding like a decorative overlay of pigment. The marks do not merely smear across the surface; they create depth within the support, anchoring the ‘image’ and preventing it from floating away, detached from its presence. They supplement the figure but often interrupt it, continually reaffirming the physical thickness of the painting itself.

This physical thickness, metaphorically speaking, becomes a garment for the figure (for the painting) itself. It could be argued that the veil enveloping the painting’s body—the veil itself—is problematized in KIM’s artworks. In this exhibition, the canvases are particularly enormous, often approaching or even surpassing the height of most people. Consequently, viewers are compelled to examine the paintings up close, focusing on specific parts rather than viewing them as a whole. This proximity activates the sense of touch, bridging the gap between the image and the viewer. As one closely scrutinizes the painting, they progressively perceive layers or veils, from the outside in. This applies both figuratively and physically, as the veils—composed of elements like clothes, skin, wings, vines, ropes, etc.—obscure not only the figure but also the canvas itself, with its width, height, and thickness.

The material layer of the painting, functioning as a sort of veil, warrants further elucidation. This layer, constantly demanding attention, provokes a desire to peel it away and look inside. The painting stimulates this urge to peel back the layers, ultimately revealing the body. However, this body is only unveiled in complex relation to its covering. In each painting, the body is depicted as problematic, both figuratively and physically. Figuratively, parts such as arms, legs, and the waist—where curves are emphasized—are exaggerated, and lines pierce or even penetrate the body, making it appear mutilated, distorted, and deformed. Physically, the veil accentuates the painting’s strata and obstructs the instinctive desire to discern a clear shape, leaving only its texture, color, light, and volume.

The distinction between clothes and body—skin, muscles—is not always clear in these paintings. For instance, in Metamorphosis (2024), blue bikinis are depicted, but there are also ambiguous blue marks on parts of the arms, legs, and chest. These marks, which could be interpreted as clothing, also resemble ribs, turning the body inside out and exposing skin or deeper muscle fibers. As these fiber strands radiate from the body, seemingly tearing through a mass, the figure overcomes its stationary posture and appears to writhe and move. The face is out of frame, preventing any exchange of gaze, and the ambiguity between clothes and body—what covers what, and what is visible?—forces viewers to engage with the painting rather than remain passive observers. The body, seemingly writhing in pain, is on the brink of transformation.

Transform into what? We may not know, but the sense of transformation prompts us to view the image as a potential state, always in motion. It might seem that we are awaiting the revelation of “nudity” in front of the paintings. Giorgio Agamben argued that “nudity” is not a state but an event, recognizable only when the body is “being unconcealed” of its coverings (clothing or grace)[iii]. In the painting, the figure is not truly “nude,” nor is there a static “nakedness.” Instead, the intertwined skin, body, and clothing act as a veil that covers each other, preparing for the eventual lifting of this veil, the body’s transformation, and the emergence of nudity itself.

Is “nudity” obscene? In these paintings, we again encounter archetypes of female characters designed for mass consumption. Often depicted as obscene and validated as voyeuristic and fetishized objects under the male gaze, these bodies are reexamined in KIM Minhee’s work. She inserts herself into these clichéd representations, which might seem unavoidable, yet she seeks to uncover new dimensions of pleasure by recalibrating them. The gaze of the Other, which once confined the body, might now serve as an impetus for a form of nudity that exposes muscles and viscera, blurring the boundaries between the world and the body.

In Berserker, we witness the body through a process of uncovering: in paintings where veils of matter create gaps in the material, stripping the image of its familiar shape, the female body engages in a dynamic play of veils. Can the body materialized in these paintings achieve a dialectic that transcends both desire and image? Here, the body, as an image-mass, is presented solely for exhibition.

Hur Hojeong

[i] Marguerite Duras (trans. by Barbara Bray), The Malady of Death (NY: Grove Press, 1986), p.32.

[ii] If you engage with digital content regularly, you’ve likely encountered temporary glitches, like a cracked or frozen screen. These audiovisual traces of perceived error (bugs or glitches) have served as a catalyst for many artists. Initially, glitches were viewed as an anti-establishment break in a smooth circuit, or their contingency and lack of material basis seemed to imply more freedom. However, over time, glitch has evolved into an aesthetic and is embraced across cultures. Now, glitch is not merely a gap in the circuit but rather an accessory, once again integrated into a larger flow.

[iii] See, Giorgio Agamben (trans. by David Kishik, Stefan Pedatella), Nudities (Stanford University Press, 2011).